Re-mixing local news – a work in progress

I’m currently researching community newspapers and magazines from the 1970s and 80s in Birmingham. Revisiting this era is timely, I would argue, because we’re in danger of abandoning the values of alternativity shown in these publications in favour of a more homogenous idea of the value of local media.

We need solutions to sustain local public interest news, argue academics (see the News Futures project out of UCLAN), politicians (see the recent DCMS report), and civil society organisations (see the Public Interest News Foundation). Yes, of course we do, given the business model for such journalism is recognised by everyone as just about broken.

The solutions being suggested are all very much top-down ones, appropriate, given the money is usually always to be found at the top. But before we presume what it is that local audiences need, I thought it worth looking back to another moment when local media was felt to be monopolistic and out of touch.

The early 70s to early 80s saw a modest range of city-wide and suburban publications collectively contribute to something an alternative public sphere of information, enlivening a rather conservative news culture, largely dominated in my city by the Birmingham Evening Mail. By this time, the suburban mainstream newspapers which had flourished after the turn of the nineteenth century had largely disappeared. As Rachel Matthews notes: “commercially motivated owners consolidated their positions by buying multiple titles to create monopolistic business models” (2015).

The community press wasn’t a focused, coordinated alternative movement, rather, a loosely connected period of disruption to normative ideas of what local news is and how it should be presented. It was messy: a mix of funded and voluntary efforts, free and paid for publications, some serious, some trivial, some born from the counter-culture movement of the 60s, some born out of feeling ignored by mainstream local publications, some with great writing, some with terrible writing.

My interviews for this research project are at an early stage, but the key themes are tantalisingly emerging. Firstly, there’s more to the material nature of these publications that the printed matter. There are golf ball typewriters, Letraset, rooms in houses and community centres used for layout, newsagents, a former squat repurposed as offices, printing presses, even activist students helping out.

Secondly, there is emotion. There are stories of being inspired by colleagues who have passed away, stories of being ignored, being bored, being angry.

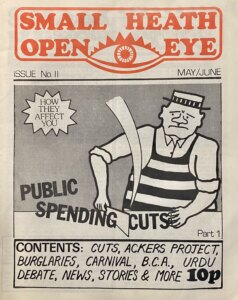

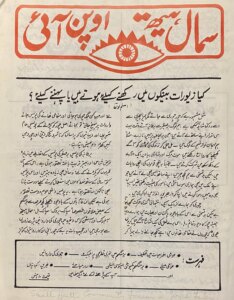

And of course there are the newspapers themselves. Encountering them in their physical form (few are digitised) brings home the lack of a collective sense of what local news should be. They look the same, but different. Some try to mimic the look and feel of newspapers, but limitations in experience and technology results in something closer to the feel of a zine at times (Small Heath Open Eye in English and Urdu, circa 1980, and Saltley Gas, mid-70s being good examples of that).

City-wide publications were more carefully designed, with Streetpress (early 1970s) incorporating full-page, arty, illustrations among articles on corporal punishment in schools and the rights of traveller communities.

Editorially, each of the publications in their own way both imitate and re-imagine local news. In between its kids pages and crossword page, the April 1976 issue of The Moseley Paper rails against elitism in the local arts scene with the Midlands Arts Centre as its target. Handsworth’s Trapeze uses the front page of its April 1973 edition to challenge media coverage of the sentencing of Paul Storey, Mustafa Fuat and James Duignan, whose cases would later be discussed in Stuart Hall’s et al Policing the Crisis, 1978. Elsewhere it had the lighter content one might expect from a local newspaper, listings, recipes, a letters page.

If the publications share anything, then it’s a broad aim to reflect place in ways that mainstream local media didn’t seem able to, perhaps because it lacked knowledge of, and contacts within, Birmingham’s diverse communities. One interviewee, who had worked on the Urdu language newspaper Saltley News as a 16-year-old in 1976, offered an anecdote in response to my question on how well he felt newspapers represented his community:

“On the corner opposite was a newsagent. Outside, there was a newspaper. It had the word Kashmir written on it. I bought it because I clearly knew this was going to say something about Kashmir. Because it was so rare for that. Kashmir was a horse. This word, Kashmir, when you fold the newspaper, it was on the back pages. With the sports pages” (Karamat Iqbal).