Materialities – The Stuff That Helps Us Remember

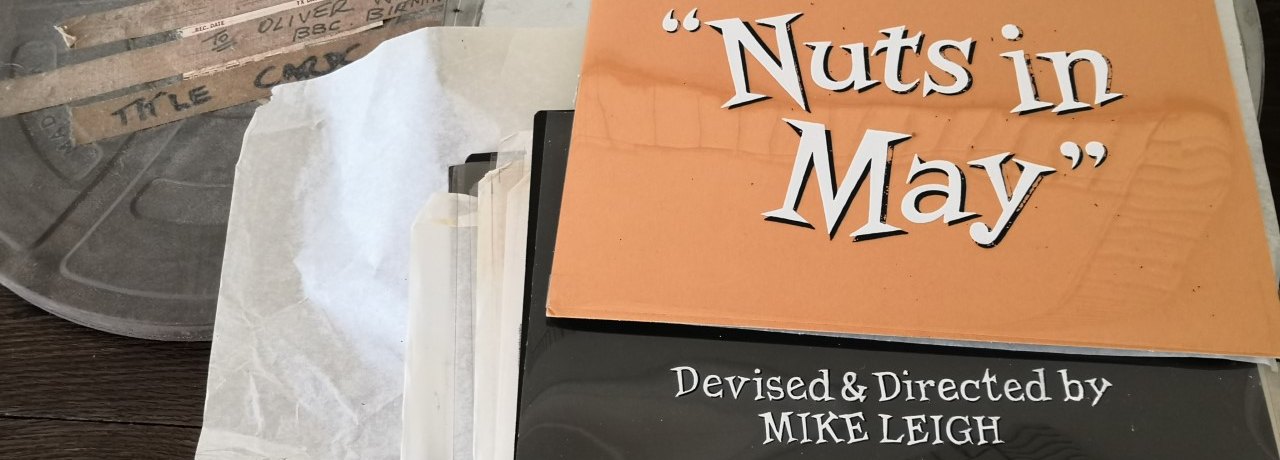

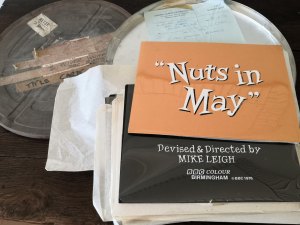

‘Nuts in May’ title cards

Running an idiosyncratic archive, http://pebblemill.org and its associated Facebook page, I’ve unwittingly become the repository for a lot of stuff, both physical and digital. As we learn from Daniel Miller, ‘the best way to understand, convey and appreciate our humanity is through attention to our fundamental materiality’ (2010), so that ‘stuff’ has great significance.

Former BBC staff clear out their lofts and find boxes of BBC Pebble Mill related items, photographs, scripts, caption cards, all manner of stuff which they are often happy to share or give to me. Material documents: a letter of disgust from Mary Whitehouse, the title captions of Nuts in May, several scripts of All Creatures Great and Small, are occupying quite a lot of my cupboard space, and so despite a passion for the physical objects, I, (and my husband) have developed a preference for digitised versions of the analogue artefacts.

The digitised artefacts (immaterial materials) are key to how my community archive works. In order to engage the online community that has grown up around the Pebble Mill project, each website or Facebook post must have a focus, and specifically a visual focus, as my research has shown that a photograph or video, elicits a far better response in terms of comments and ‘likes’ than a purely written one. The indexicality of photographs seems to make them a stimulus for remembrance. John Berger describes the ‘thrill’ of seeing a photograph that brings an ‘onrush of memory’, and that is what seems to happen in a communal context on social media.

Paula Uimonen draws cultural similarities in terms of visual identity between traditional, hard-copy photograph albums and social media profile pictures (2013, p. 134), I argue that this analogy extends beyond profile pictures to the operation of whole Facebook Community pages, like the Pebble Mill one, which act like an online collective photograph album. In her work on 19th Century, and early 20th Century photograph albums, Anna Dahlgreen asserts that the older Victorian photograph albums acted as conversation pieces and worked better without text, in contrast to the Edwardian and later ones, which tend to be annotated and are akin to a personal diary (2010). Social media profiles, particularly on sites like Facebook, are the contemporary equivalent of those later annotated albums, and it is significant that Facebook even uses the same language of ‘photo albums’, and encourages annotation with the message to ‘say something about this photo’.

I see my role as guardian of the community’s (online) photo album, sharing the photos and other digitised artefacts with the people they have meaning for, responsible for keeping the stuff that evokes those collective memories – both physical and digitised, of BBC Pebble Mill safe.

Berger, J. (1967) Understanding a Photograph, London: Penguin Books Ltd

Dahlgren, A. (2010) Dated Photographs: The Personal Photo Album as Visual and Textual Medium, Photography and Culture, 3:2, 175-194. Oxon: Routledge

Miller, D. (2010) Stuff. Cambridge: Polity Press

Uimonen, P. (2013) Visual identity in Facebook, Visual Studies, 28:2, 122-135, Oxon: Routledge