Digital games, adaptive tech and materialities

One goal of the cross-faculty Simulation and Games Network at BCU is to use our meetings for more than sitting in a room and discussing ideas. To that end, for our first meeting of the year we took ourselves to the Hacked! exhibition at BOM, to see a range of digital games that had been made with accessibility in mind or were set up to play with adaptive controllers. There were also a few displays of adaptive tech for musicians, which overlapped as a tech solution.

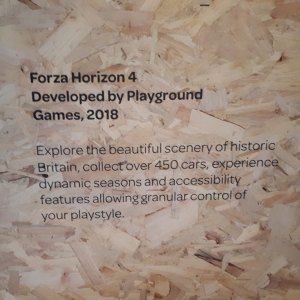

All of the games were playable, which meant that we got to engage in some hands-on research. Forza 4 played fairly well with a single joystick and separate accelerate/reverse switches, though navigating the game options was complicated. Other AAA titles had moderate playability, and I found that muddling through a training level was a fair way to find my way around a deconstructed controller array, but exploring an open world was frustrating since I was relying on muscle memory of a Playstation controller that was now distributed across two joysticks and a button pad.

With this year’s materialities theme in mind, this exhibition is a keen reminder that gamers exist as bodies in space. Attempting to play a AAA game ‘normally’ highlights problems that arise when interacting with digital objects that presume the user has an abled body. These examples did more to articulate the difficulties of inclusive design that to provide a seamless user experience.

Overall impression: that the most successful instances of tech looked like the adaptive solutions for musicians, demonstrated via documentary clips, but with the artefacts on display. For example, a baton that would allow professional musicians to follow a conductor. Otherwise, the exhibition is a reminder of the complexities of designing or adapting games for players with different physical abilities: being familiar with Playstation controllers, having the adaptive controllers mapped with descriptions of functions rather than the button labels was unintuitive.