Who cares? Thoughts on Facebook’s Care Reaction

This piece was co-authored with Dr Jacob Johanssen of St Mary’s University.

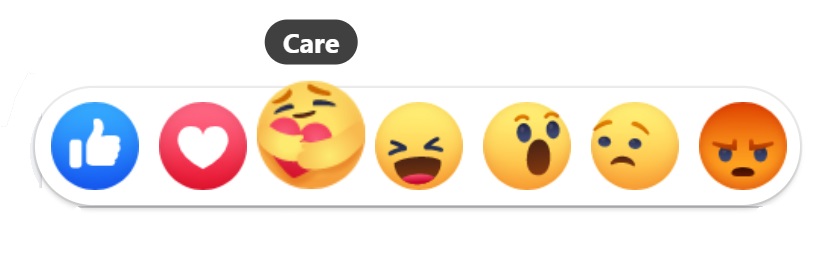

On 02 May, Facebook introduced a new “reaction” emoticon in addition to the already existing six (like, love, laughter, surprise, sad, and angry) which users can select on the main platform and on Messenger when interacting with others: Care. The Care emoticon has been rolled out seemingly specifically as a response to the Covid-19 pandemic that is shaking the world. At a time when people must be apart, Facebook’s caring figure – a cute smiley that lovingly hugs a red heart – is a symbolic expression of affective feeling. As a Facebook technical communications manager noted on Twitter:

We know this is an uncertain time, and we wanted people to be able to show their support in ways that let their friends and family know they are thinking of them.

— Alexandru Voica (@alexvoica) April 17, 2020

Upon being used for the first time, the following message appears: ‘We’ve added a new reaction so you can show extra support while many of us apart. We hope this helps you, your family and your friends feel a bit more connected. – The Facebook Team’. However, while the Care reaction could be seen as a meaningful way to share love, care and compassion with others on Facebook in times of COVID-19, it is important to point to underlying mechanisms beneath a simple emoticon. What is Facebook’s aim and how does the Care reaction relate to its business model? How is care communicated on social media today? Is care the adequate response to crises, uncertainty and death? Those questions are explored by us in this piece.

Facebook is a company that is reliant on user data in order to enable targeted advertising. User data are shared with advertisers who pay Facebook in order to provide custom ads to individuals. While users have recently been provided with more tools and information on how they can opt out of targeting, the core advertising business model has remained unchanged. Facebook has, especially in light of scandals such as the Cambridge Analytica case, always been keen to portray itself as a platform for communication and connection, rather than for making money off user data. The Care emoticon can thus be seen as a logical step in a strategy that is about the portrayal of Facebook as a caring facilitator. As Alexandru Voica, Facebook’s technical communications manager, noted:

While this Reaction is temporary for now, there is a chance we will make it permanent as we know showing care on Facebook isn’t just tied to one moment.

— Alexandru Voica (@alexvoica) April 17, 2020

Facebook may be providing a free service that enables connection, exchange of opinions and even care between people, but it is also keen to find out about users’ emotional and affective states when liking or loving something, being angry about another’s post or expressing care. Under the guise of sharing support, Facebook will be capturing more and more data that specifically tells them what you “care” about. Careacting is handing Facebook more of your personal data – your ideologies, your empathetic triggers – so that Facebook can benefit, through targeted advertising. In selecting the Care smiley, we provide more quantified data about our affective states, something the platform is keen to harness for surveillance and advertising purposes.

We have come to a point of what could be considered the affect economy, wherein ‘the affective surplus produced by disasters […] have become themselves part of an economy in which affect circulates as source of market opportunity for profit’ (Adams 2013: 10). Adams asks, ‘how does a surfeit of emotion generated by the inefficiencies of profit in recovery capitalism become itself drawn back into the economy as a new resource for profit’ (2013: 124). The answer is epitomised by Facebook’s “care” reaction – the surfeit of emotion becomes captured and financialised by Facebook – not the NHS, or key workers, but Facebook.

Two questions are important to ask: What does the Care reaction really express and what does it capture?

In a sense, Facebook frames the current situation in a positive manner by encouraging us to care for others and express it. What does care really signify in this context beyond its immediate act of showing compassion?

Care has acquired value as an expression of public support in times of Coronavirus, for example by clapping for NHS and other key workers every Thursday. Such performative expressions of care are opportunities for us to show that we support and value others, particularly those in caring professions. But they ultimately remain mere gestures that risk diminishing the real care that is performed by underpaid, precarious workers in the NHS for instance. The expression of “care” has almost overtaken and obfuscated the need for that care to become financial – “care” becomes exploited for the purposes of news stories, a seeming sense of solidarity that suggests “we are all in this together” whilst attempting to cloud the inequalities, shortfalls and financial quantification of “care”. Selecting an emoticon or clapping in the street should not be seen as adequate expressions of care. They mask the real care that takes place elsewhere.

Conversely, there is an aspect of virtue signalling inherent within the performative aspect of the click, it becomes a form of clicktivism that lacks effect and could be linked to the attention economy – a form of bandwagonism, “look at me, I too care”. This becomes part of the presentation of self in online contexts, establishing one’s “brand” yet calling into question the authenticity of such outputs. Facebook isn’t encouraging actual care, but the expression of care – and this is political. Political both in its echoing of current politician’s rhetoric vs. their ideologies, and political in terms of the harnessing of affect for financial gain, as mentioned above.

On the other hand, the ways in which the careaction operates capitalises on the affective feelings and experiences of its audience whilst detracting from the affective labour involved. Facebook’s statement that you can ‘show extra support’ and ‘feel a bit more connected’ through the simple act of clicking-to-care does nothing to actual acknowledge the stress and strain of being apart or of experiencing a world in crisis. This affective labour is demonstrated across social media through posts discussing exhaustion, depression, anxiety and sorrow. Coming to terms with life in the times of Covid-19 has left many feeling isolated and bereft, and others feeling hopeless and useless. There are therefore issues around a possible demand to show care. There may be individuals who are unable to show care because they are too exhausted, grieving or feel uncared for themselves. Some also may not care at all or feel that a gesture is not enough to express real care. The cost of “care” is real, and the quantification of clicking-to-care fails to open this dialogue up.

Social media can, then, already operate as a significant outlet for care, support, and encouragement, but often this is facilitated best through the genuine discursive exchanges that occur on Facebook, rather than the demand for a performative “reaction” – there is no doubt that many have positively benefitted from the sense of community on social media and after all, that is supposedly the reason these sites were created in the first place. One of the most significant moves that the platform itself has taken to demonstrate “care” is through the creation of its ‘Coronavirus (Covid-19) Information Centre’ which operates as a hub for facts from verifiable sources, links to government information, headlines regarding the virus, and a way to link those needing help to those offering it. This is the most significant step that Facebook have taken, along with the removal of pages promoting harmful misinformation.

References:

Adams, V. (2013) Markets of Sorrow, Labors of Faith. London: Duke University Press.

Follow Dr Poppy Wilde on twitter @PoppyWilde and Dr Jacob Johanssen at @Jacob_PhD for more of their work.