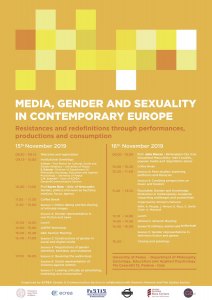

ECREA Gender and Communication Conference, University of Padua, 15th-16th November 2019

As part of the ‘Queering the Audiovisual’ panel at the ECREA G&C conference, I delivered a paper (co-written with Dr Gemma Commane) on the performance of failed femininities in RuPaul’s Drag Race (Logo TV, 2009-2016; VH1, 2017-present). ‘“I can see your seafood platter”: RuPaul’s Drag Race and the performance of ridiculous femininity’ explored how male drag performers in the show can pick and choose what feminine ‘failings’ or aesthetics they display as a means of gaining success, but also how that picking and choosing is a privileged position. At the same time, when the contestants fail to achieve these assumed feminine aesthetics or excess, they are judged in the same way as women in the wider world who are seen to fail.

Our paper argued that while the show is celebrated in challenging gender norms and renegotiating discourses around masculinity, in doing so it re-inscribes hegemonic discourses around femininity. Femininity is often presented within the confines of RuPaul’s Drag Race as ridiculous and we explored the commodification of female bodies, stories, tragedies and failings. While drag is presented in the show as a space of possibility, this is only a possibility for male performers who are able to exploit the ‘failings’ of women. ‘Ridiculous’ women are often denigrated as laughable and disgusting through the challenges which the queens undertake, notably the Snatch Game. Another underlying discomfort is how ‘good’ female bodies (thin, beautiful, middle class, often white) are validated. Lip-sync performances are often sexualised with a lot of talk of ho’s, accompanied by commentary from judges on their bodies, blow jobs and sluttiness.

Alyxandra Vesey (2016) and José Esteban Muñoz (1999) criticise RuPaul in relation to the commodification of gay culture and RuPaul’s celebrity being far removed from queer radical politics. The maintenance of fame and success is therefore continually negotiated by and through templates which are set by RuPaul within the context of community culture, celebrity and pop stardom, and this is framed through and measured by success. Queens have to comply with standards that are marketable and palatable for a wider non-queer audience. Palatability also means drawing upon and circulating normative gendered, classed and raced discourses that are intelligible to help audiences reaffirm value systems on queens, and forms of femininity that are historically shamed, laughed at or celebrated.

According to Gøsta Esping-Andersen people are commodified or ‘turned into objects’ when selling their labour on the market to an employer. In RPDR, femininity is turned into an object to be traded for capital (or wins) in the show. The maintenance of fame means queens need to continually market and prove themselves, and while they might come into the competition with a particular way of doing things or a particular political stance, the format of the show (it’s a competition) means that they often have to conform or make compromise in order to be positively judged. Often this compromise leads the queen contestants to have to present their drag in accordance by the feminine aesthetic promoted by the show.

For most of the contestants (a notable few have come out as transgender) living as a woman and experiencing critique from friends, family and the wider media isn’t a day to day concern. This compromise, or ability to change up, draws attention how the contestants have a privileged position as men to pick and choose the feminine aesthetic they want to show. We concluded that whilst the show is celebrated as an unstable space for possibility in terms of gender norms, our paper sought to demonstrate that it is, in fact, very fixed in terms of the femininities which it presents (i.e. female otherness, transphobia, BAME stereotypes, etc).

This was my first academic conference outside the UK and Northern America, and I was struck by the different issues and attendant questions which emerged over the two days. The conferences which I have previously attended have been dominated by UK and US voices, as well as a pre-occupation with media texts which have emerged from those UK and US media industries. With a European focus, this conference provided an important opportunity for those voices and cultural contexts to become less hegemonic, which created a space for some interesting discussions of what it means to be a European researcher in a field dominated by UK/US programming across a variety of papers and panels. My own panel included a call to arms to researchers to consider the media texts which have originated in their home countries, noting that this is a moment of potential for creating a richer and more diverse media studies landscape. The ‘Queering the Audiovisual’ panel ended in an unexpected discussion about the future of PSB in the UK and the concerns which our European neighbours have for the UK in the current political climate, as we made links between what is valued in media content creation and isolationist individualism. For me, this discussion was indicative of what was a thought-provoking conference. It cast a light upon the losses caused by Brexit which exist outside the economic or questions of sovereignty, reminding me of the rich, once-shared, intellectual community which the UK’s departure from the EU may damage.

Bibliography

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Muñoz, J. E. (1999). Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Vesey, A. (2017). ‘“A Way to Sell Your Records”: Pop Stardom and the Politics of Drag Professionalization on RuPaul’s Drag Race.’ Television & New Media, 18(7), pp.589-604.