The Iconography of Jazz and Photography

by Brian Homer

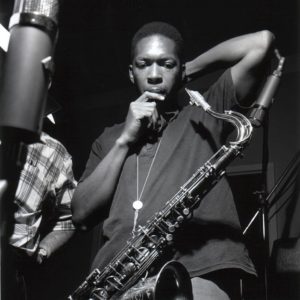

My proposal is that the styles and techniques of photography translated into the use of photography in jazz made a profound impact on the iconography of jazz and how we view jazz. To illustrate this I am going to take some selected examples of jazz photography and look at how they were possibly influenced by other photographic uses. First, I am going to take the iconic image of John Coltrane taken by Francis Wolff, and used on the cover of Blue Train, by the designer Reid Miles.

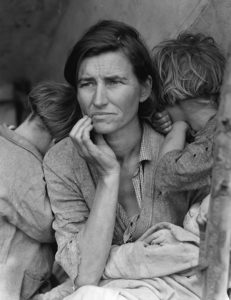

The Blue Train session took place in 1957. The image chosen shows a reflective Coltrane with his hand to his chin looking down and intent. His sax is slung across him. This image is not in the common language of the gig/playing image that is very prevalent in jazz. Rather, I would argue that this image is in a documentary photography style and has similarities to Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Woman image (1936) taken California while working for the Reconstruction Administration (later the Farm Security Administration) of a destitute and starving family.

The mother has her hand to her chin and is looking reflectively to her right with two of her children either side of her but facing away from the camera. The effect is very similar in both images – allowing the viewer into the picture to speculate on what is going through the mind of the subject. Wolff was a migrant from Germany and being a keen photographer would, no doubt, have been exposed to the documentary styles becoming prevalent in Europe and the USA.

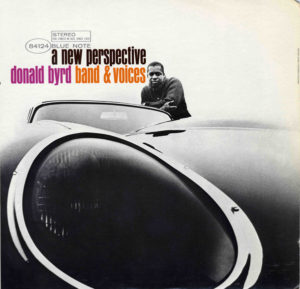

Turning to the cover of Donald Byrd’s A New Perspective, also on Blue Note from 1964, a different photographic influence is at play. By this time, corporate identity and conceptual graphic design were developing rapidly. In this shot, by the designer Reid Miles, the main element is not the musician but the eccentrically shaped headlight cover of a Jaguar E Type, situated in the bottom left of the image. The lines of the bonnet, wings and windscreen lead to Byrd.

This kind of wide angle shot is unusual for the time. I suggest this was influenced by Russian Constructivism. Photographers in that movement were looking for modern, futuristic ways of representation that would foreground progress and technology; to achieve this they used angles, shadows.

European emigré designers and artists came to the US during the 1930s; one of these was Russian Alexey Brodovitch. Brodovitch became the designer of Harper’s Bazaar and in his layout style and use of photography was very influential. He taught many photographers including Irving Penn and Richard Avedon and while there is no evidence of a direct link to Miles it would not be surprising if in the creative milieu of New York in the 50s and 60s such influence rubbed off on an up and coming designer.

I’ll finish with two questions:

- First: does jazz photography now have an impact on how we perceive jazz?

- Second: are jazz photographers like me missing a trick in concentrating mainly on performance pictures?

Both of these would bear further study.

Brian’s paper was delivered on 28 February 2018 as part of the BCMCR Seminar Series.