GUEST POST: Kevin M. Flanagan on ‘Translating Chrono Trigger’

Adapting and Translating Chrono Trigger Across Time

by Kevin M. Flanagan

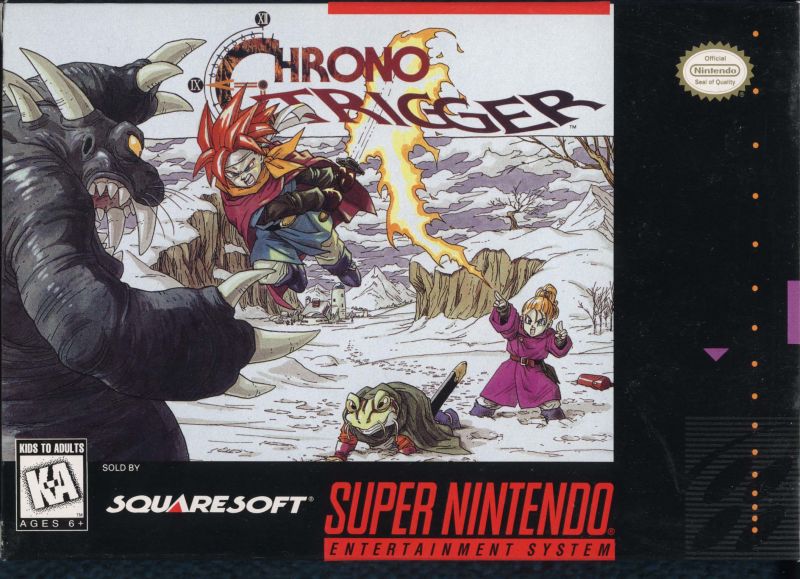

This short piece is meant to introduce readers to what is at stake when we talk about adaptation and translation in relation to videogames. It is meant to summarize material explored in greater depth in both my chapter in the Oxford Handbook of Adaptation Studies (2017) and the issue of Wide Screen Journal that I edited in 2016. In the interest of keeping things as coherent as possible, I’ve opted to highlight some “pivot points” in adaptation and translation as applies to one specific game: Chrono Trigger, a Japanese role-playing game (JRPG) developed by Square and originally released for the Super Nintendo/Super Famicom console in 1995. The game follows a silent protagonist, Crono, across many different time periods, and includes choices that affect the outcome of the narrative (there choices about whether or not to take characters, and the player must consider how their actions in the older timelines affect the world in later periods). Crono and his fellow adventurers are thrust into a high-stakes quest wherein they must thwart the primeval Lavos, a monstrous being that seems destined to destroy the world. In a somewhat rudimentary and scripted (though surprising–especially for 1995) way, the game can be said to “adapt” to player choice, and players who opt for different choices will find that their endgame, and the fate of the world, can be quite varied as compared to other playthroughs.

A look at Chrono Trigger’s conception, release, and afterlife–it is a much-loved game that Square has tried to keep available in various ways over the past two decades–indicates that to speak of “videogame adaptation” is to speak of a whole process that happens at many different levels.

A conventional place to start is to focus on production. In a loose sense, Chrono Trigger is an amalgamation of influences (The Time Tunnel, Alien, Quantum Leap, etc), yet is mainly regarded as an original intellectual property (in other words, it is not a one-to-one adaptation of a specific text). For lead designers Takashi Tokita, Akihiko Matsui, Yoshinori Kitase, and producer Kazuhiko Aoki, it is the game is a deliberate innovation within a cultural defined tradition, the console JRPG, a genre that the team had practically invented over the previous decade. While there is much more to the game’s conception and production–the Wikipedia article gives a thorough overview–it is worth highlighting how one key element of a videogame is the sometimes ultra-narrow specificity of playability: Chrono Trigger was designed for a specific platform, and as the game has been released for new platforms and devices (the Playstation, the Nintendo DS, the Wii Virtual Console, Steam), the game is adapted anew to suit the technological specifications of its new operating system. Thus, one key moment is tracking how a game is adapted/readapted as it is “ported” to new platforms. This sometimes requires that key assets be re-thought: “updated” graphics, a remastered soundtrack, and so on. One of the paradoxes of videogame adaptation is that what may be regarded by programmers and producers as improvements are often disliked by players. For instance, graphical alterations for the recent Steam port were so disliked that Square patched the game so that it would look more like the original SNES version.

This brings up another key pivot: the degree to which videogame users and fans translate and adapt games in their own ways. For Chrono Trigger, this means two decades of fan creative production that adapts, updates, expands, re-emphasizes, and edited the game to taste. Chrono Trigger has inspired extensive fan fiction, from a poem about peripheral character Cyrus to an attempt at officially adapting the game to novel form. The practice of “rom hacking” has allowed fans to build new games using the engine and assets of the original. One high profile example is Chrono Trigger: Crimson Echoes, which is as yet unfinished.

A key form of adaptation for the “cultural translation” project is localization, the process by which a game is made to suit a new regional or cultural market. Going beyond what might generally be regarded as the remit of translation, localization often opts for familiarity and specific literacies over strict accuracy. For instance, in adapting the Famicom game Saiyūki World 2: Tenjōkai no Majin (in its original form, itself an adaptation of Sun Wukong’s Journey to the West narrative that is so central to Chinese folklore), Jaleco completely re-skinned the sprites, remade the protagonist as a somewhat culturally insensitive Native American warrior, and gave the game the punny title Whomp ‘Em. Localization work on Chrono Trigger across its various releases has been less dramatic, but still fascinating. Clyde Mandelin writes about how the English translations for the valorous knight Frog took liberties in emphasizing his courtly manner of speech that were not literally apparent in the Japanese version. Fans have tracked the differences in versions with characteristic zeal, noting differently named items, characters and dialog with changed implications.

The above just scratches the surface of videogames’ engagement with issues of cultural translation. For instance, a sociologist might study the cultural-symbolic value of videogames in different parts of the world, or an art historian might go in-depth on how iconography gets reimagined as games are released in parts of the world with different dominant religious associations.

Kevin M. Flanagan is a Visiting Lecturer in the Department of English at the University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

GUEST POST: Andrew Bain on ‘Teaching – Playing – Researching’

by Andrew Bain

‘Playing and listening to music together provides a cultural space and a cognitive means through which individuals and social groups can coordinate their actions and behaviours’. (Borgo, 2006: 5)

As David Borgo (Sync or Swarm, 2006) alludes to above, the very act of ‘playing’ is a coordination of actions and behaviours, and I ask to what extent is the simple act of ‘playing’ in a group improvised context informed by a reservoir of improvisational knowledge alongside a keen awareness of intelligent transactions? My third and final PhD case study asked these very questions. Completed in December 2017, the project featured improvising musicians Peter Evans (trumpet), John O’Gallagher (saxophone) and Alex Bonney (electronics) in a freely improvised setting with no composed music, no rehearsal and no pre-conceived ideas. We simply played. But what does it mean to ‘simply play’? And is it even possible to have no boundaries within improvised group performance?

As a player, my greatest challenge is finding a way to develop group improvisation; as an educator, my greatest challenge is passing on the tools needed to do the same thing. In my roles as senior lecturer, jazz drummer/composer and emerging researcher, I have been dealing with this confluence for some time. At the heart of my playing and research is the cultivation of an active connection with my conservatoire jazz students aiming to maintain an open dialogue about my mode of working and its relevance to their personal evolutions. In my final thesis chapter, I ask, to what extent has this been successful, and how can my findings contribute to further good practice in higher education?

A graduate of the Guildhall School of Music & Drama, London and Manhattan School of Music, NYC, Andrew Bain has performed with many luminaries of the jazz world, and in many major festivals, on both sides of the Atlantic. Andrew is Senior Lecturer in Jazz at the Birmingham Conservatoire and Artistic Director of Jazz for the National Youth Orchestras of Scotland.

GUEST POST: Esperança Bielsa on ‘Linguistic Hospitality’

by Dr Esperança Bielsa

(this is an extract from E Bielsa and A Aguilera, ‘Politics of Translation: A Cosmopolitan Approach’, European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology, 4:1, 7-24.)

The fundamental ethnocentrism of translation, the reductive tendency that is present in any culture, makes it necessary to formulate a politics of translation in any cosmopolitan project. A politics of translation based on the ethical purpose of translating, which according to Berman is to open up in writing a certain relation with the other, to fertilize what is one’s own through the mediation of what is foreign. Invoking Derrida’s notion of hospitality, Ricoeur has stated that translators can find happiness in what he calls linguistic hospitality, appealing to a regime of correspondence without adequacy that does not erase the irreducibility of the pair of what is one’s own and what is foreign. Only linguistic hospitality understood as an absolute or unconditional hospitality that lets the strangeness of the foreign tongue arrive and does not hide it under a pretended equivalence or false familiarity will make it possible to fertilize what is one’s own through the mediation of what is foreign. Absolute hospitality, as Derrida points out, breaks with the law of hospitality as a right or as a duty. Beyond the obvious reason that an ethical translation of the other, that is, a translation that does justice to the difference of the other, is not contemplated in any regime of rights, one would need to approach a politics of translation based on linguistic hospitality as a responsibility and not as a right. In many instances, this responsibility not only anticipates the law, or is even positioned in certain cases against the norm so that justice can be done, but refers to the circumstances and conditions in which genuine communication can be established. This cannot be articulated from a rights based approach, which approves of any type of communication as long as nobody’s rights are infringed.

An identity that reveals a glimpse of linguistic hospitality could avoid an identity that autoimmunizes itself in processes of closure, of a repetition that is assumed to be eternal but is still ephemeral and fragile, only less flexible and often less resistant and capable of survival. What at the philogenetical level distinguishes intelligence from instinct is not much more than this flexibility, which is impossible to sustain through the preservation of a dogmatic core of origins and essence that the old identitarian identity serves as an idol. There is no lasting tradition that is not renewed by the foreign. Linguistic hospitality allows for this innovation without parting blindly with what deserves to be preserved. Thus, linguistic hospitality could be the core of a politics of translation that is open to the foreign, neither closed nor absolutely open. Where Derridean hospitality would invoke a negative theology without any remaining borders, and where Habermasian tolerance would demand equality across borders, a politics of translation centred on linguistic hospitality draws a porous border in a cosmopolitan space. It really follows a perspective that has led the last Derrida to preserve a minimal nation-state in an international context, and Habermas to insist on a cosmopolitan constitution with few remaining borders. In its short distance from real hospitality, such politics of translation could give social shape to welcoming foreignness, conform it in language, that material of our wakefulness and dreams, of collective longing, that has modified and stirs our flesh, sending it beyond a spirit conceived as mere ideality, beyond culture as a mere symbolic game.

About the contributors: