Adapting and Translating Chrono Trigger Across Time

by Kevin M. Flanagan

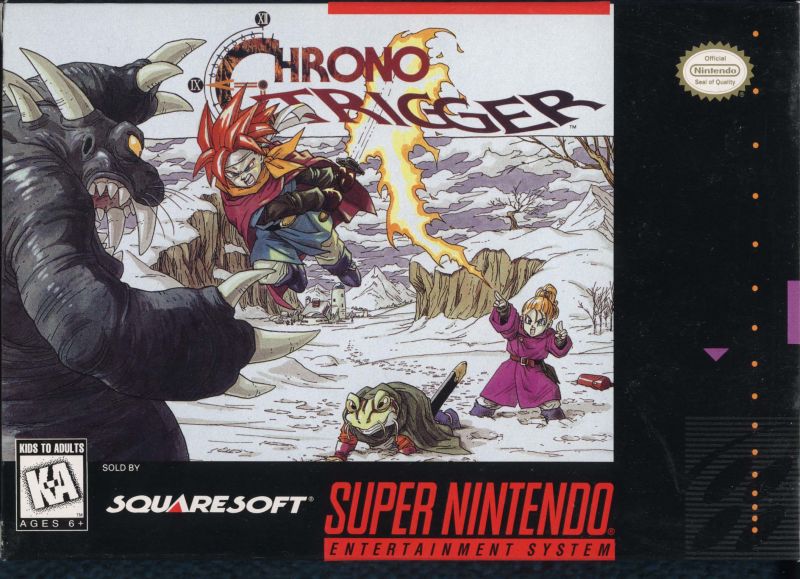

This short piece is meant to introduce readers to what is at stake when we talk about adaptation and translation in relation to videogames. It is meant to summarize material explored in greater depth in both my chapter in the Oxford Handbook of Adaptation Studies (2017) and the issue of Wide Screen Journal that I edited in 2016. In the interest of keeping things as coherent as possible, I’ve opted to highlight some “pivot points” in adaptation and translation as applies to one specific game: Chrono Trigger, a Japanese role-playing game (JRPG) developed by Square and originally released for the Super Nintendo/Super Famicom console in 1995. The game follows a silent protagonist, Crono, across many different time periods, and includes choices that affect the outcome of the narrative (there choices about whether or not to take characters, and the player must consider how their actions in the older timelines affect the world in later periods). Crono and his fellow adventurers are thrust into a high-stakes quest wherein they must thwart the primeval Lavos, a monstrous being that seems destined to destroy the world. In a somewhat rudimentary and scripted (though surprising–especially for 1995) way, the game can be said to “adapt” to player choice, and players who opt for different choices will find that their endgame, and the fate of the world, can be quite varied as compared to other playthroughs.

A look at Chrono Trigger’s conception, release, and afterlife–it is a much-loved game that Square has tried to keep available in various ways over the past two decades–indicates that to speak of “videogame adaptation” is to speak of a whole process that happens at many different levels.

A conventional place to start is to focus on production. In a loose sense, Chrono Trigger is an amalgamation of influences (The Time Tunnel, Alien, Quantum Leap, etc), yet is mainly regarded as an original intellectual property (in other words, it is not a one-to-one adaptation of a specific text). For lead designers Takashi Tokita, Akihiko Matsui, Yoshinori Kitase, and producer Kazuhiko Aoki, it is the game is a deliberate innovation within a cultural defined tradition, the console JRPG, a genre that the team had practically invented over the previous decade. While there is much more to the game’s conception and production–the Wikipedia article gives a thorough overview–it is worth highlighting how one key element of a videogame is the sometimes ultra-narrow specificity of playability: Chrono Trigger was designed for a specific platform, and as the game has been released for new platforms and devices (the Playstation, the Nintendo DS, the Wii Virtual Console, Steam), the game is adapted anew to suit the technological specifications of its new operating system. Thus, one key moment is tracking how a game is adapted/readapted as it is “ported” to new platforms. This sometimes requires that key assets be re-thought: “updated” graphics, a remastered soundtrack, and so on. One of the paradoxes of videogame adaptation is that what may be regarded by programmers and producers as improvements are often disliked by players. For instance, graphical alterations for the recent Steam port were so disliked that Square patched the game so that it would look more like the original SNES version.

This brings up another key pivot: the degree to which videogame users and fans translate and adapt games in their own ways. For Chrono Trigger, this means two decades of fan creative production that adapts, updates, expands, re-emphasizes, and edited the game to taste. Chrono Trigger has inspired extensive fan fiction, from a poem about peripheral character Cyrus to an attempt at officially adapting the game to novel form. The practice of “rom hacking” has allowed fans to build new games using the engine and assets of the original. One high profile example is Chrono Trigger: Crimson Echoes, which is as yet unfinished.

A key form of adaptation for the “cultural translation” project is localization, the process by which a game is made to suit a new regional or cultural market. Going beyond what might generally be regarded as the remit of translation, localization often opts for familiarity and specific literacies over strict accuracy. For instance, in adapting the Famicom game Saiyūki World 2: Tenjōkai no Majin (in its original form, itself an adaptation of Sun Wukong’s Journey to the West narrative that is so central to Chinese folklore), Jaleco completely re-skinned the sprites, remade the protagonist as a somewhat culturally insensitive Native American warrior, and gave the game the punny title Whomp ‘Em. Localization work on Chrono Trigger across its various releases has been less dramatic, but still fascinating. Clyde Mandelin writes about how the English translations for the valorous knight Frog took liberties in emphasizing his courtly manner of speech that were not literally apparent in the Japanese version. Fans have tracked the differences in versions with characteristic zeal, noting differently named items, characters and dialog with changed implications.

The above just scratches the surface of videogames’ engagement with issues of cultural translation. For instance, a sociologist might study the cultural-symbolic value of videogames in different parts of the world, or an art historian might go in-depth on how iconography gets reimagined as games are released in parts of the world with different dominant religious associations.

Kevin M. Flanagan is a Visiting Lecturer in the Department of English at the University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.