USE HYPERLOCAL MEDIA / SAVE LIVES

A version of this appears in the NEW THINKING #3.7 pamphlet.

In 2018 I finished my PhD studying Facebook Pages of hyperlocal media organisations. At some point I also joined a Facebook Group serving the local community where I live – similarly run by residents, but as a Group, inviting perhaps even more participation than B31 Voices, but still with a hierarchy of admins ‘allowing’ posts through, or “gatewatching” (Bruns, 2003: 31).

Fastforward to the end of 2019 and I had become an admin of that Group – one of several working on a voluntary basis moderating new content and the discussions that followed. I soon experienced the backstage of a group like that, now seeing all posts that were submitted, regardless of whether we let them through, giving me a better sense of the editorial controls taking place. I was also included in the admin’s own Facebook chat, which was active most days, often used as a space to decide whether a new post fell within the group rules or not or to discuss inappropriate behaviour by group members.

I study hyperlocal media. I also co-moderate a hyperlocal Facebook group. And then covid19 happened.

I was interested here in trying to identify what I felt changed in the Group:

- Where events/evening classes/sports/fitness groups would have been advertised in the past, they were now all inactive. But interestingly, people didn’t really ask about online equivalents, sharing their loneliness or asking for other suggestions – perhaps because those online equivalents weren’t geographically localised, and didn’t require local knowledge, they didn’t feel it relevant to ask in this Group e.g. people doing Joe Wicks which was discussed on national news, rather than local fitness groups.

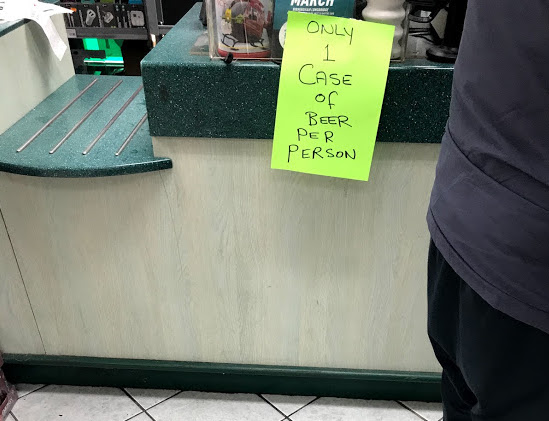

- Where the above describe some of the prior functional aspects of a hyperlocal page, the functionality changed to asking what time shops were closing and opening, what the queues were like, whether there was actually any food or toilet roll in the shops. This became a very practical aid to lockdown, meaning people didn’t leave the house if they knew it would be a wasted trip or potentially cause them harm through unnecessary exposure, hence my title: USE HYPERLOCAL MEDIA / SAVE LIVES.

- ‘Rants’ were common – people expressing frustration about others not social distancing, stockpiling, and littering. These became repetitive so we tried 1. allowing fewer such posts through the doors and 2. some stockpiling of our own, inviting all covid complaint or information comments into one ‘covid post’ at the start of each day. By this time though, such posts were starting to ease off anyway. i.e. audience behaviours were actually shifting faster than we could think up contingency/management plans for them. Also, the opportunity to rant shouldn’t be undervalued, especially for those living alone. Rants are framed as such because there’s no information or directly functional aspect of such posts, but they are social in that they allow expression, and can allow debate that distils public opinion.

- Gig economies / side hustles may have flourished or benefited. Mask makers emerged, first for charity or donation to NHS as PPE was discussed in the news, but then as a business. ‘Man with a van’ requests became more popular as people cleared out their houses, but so too did flytipping as a result, especially given that municipal tips were closed.

- Lost or ‘spotted’ pets, usually a staple of hyperlocal groups, took a backseat, and are only now just starting to return – not so much because pets aren’t getting lost as often (although this may be true as more people were at home looking after them), but perhaps reflective of what people thought was important to post in these times, what the norm of the space had become.

- People still shared local experiences. ‘Clap for carers’ on Thursday became the new version of posting photos of sunsets, as people almost competitively talked up the activity on their street – the culmination being a local musician livestreaming a full concert on his driveway.

- People sharing, requesting, or offloading things, e.g. ‘Puzzles for my nan’. Perhaps because people knew we didn’t allow ‘selling’ in the Group, people left things out in the street for others and signalled that for the readers. Altruistically? Not necessarily – for many it would have been the only way to have a clearout with tips closed.

Finally then, did hyperlocal spaces become ‘better’ as a result? Did people rally around and support each other here because it was the only space/place they could occupy locally under lockdown? I’m not sure. But I do know it happened autonomously, alongside informal mutual aid type groups springing up amongst citizens, churches, local councillors and other volunteers, irrespective of the government’s own efforts, when it has been unclear how the organisation of said army has taken place or eventually benefited communities.

Bruns, A., 2003. Gatewatching, not gatekeeping: Collaborative online news. Media International Australia Incorporating Culture and Policy, 107(1), pp.31-44.