Popular music conference season 2019: IASPM XX “Turns and Revolutions”at the Australian National University and “Rethinking Progressive Rock” at Griffith University

The twentieth Biennial Conference of the International Association for the Study of Popular Music took place in June 2019 at the School of Music at the Australian National University in the city of Canberra. Attracting participants from all over the world to travel to Australia, the conference acted as a prompt for organising a series of off-shoot, smaller-scale events after the end of IASPM XX at Universities across the country; one of them was the “Rethinking Progressive Rock” symposium at the Griffith Centre for Social and Cultural Research in Brisbane. For me, both events offered invaluable opportunities to access new research in music, enriching my scholarly and teaching practices. Building on existing professional contacts and expanding my network has outlined opportunities for developing future collaborations and allowed for promoting the work taking place at the BCMCR Popular Music Cluster and the newly established Music Industries BA course at the Birmingham School of Media.

IASPM XX

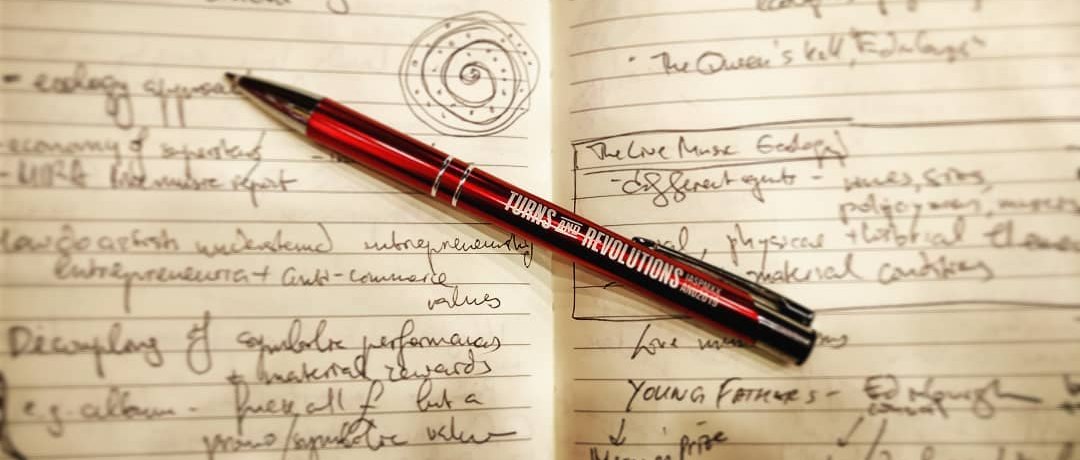

With participants from all over the world, the five-day conference under the title “Turns and Revolutions” was the result of planning and preparation that took place over four years (!), led by co-ordinator Dr Samantha Bennett and the IASPM Australia and New Zealand branch. The hard work was certainly worth it… and worth exchanging European summer for some very busy Southern Hemisphere winter days! The conference articulated the breadth and richness of popular music research. A key theme at the conference, attune to current global debates, explored the value and materiality of music and the environmental “cost” of contemporary industries, presented in the opening keynote by Matt Brennan, Kyle Devine and Jo Scott. I was particularly interested in panels dedicated to how streaming and playlist economies change music content and meaning; the challenges and opportunities encountered by live music venues in international contexts; and the place of music in the relationship between heritage and future. As a Birmingham-based music researcher, I was pleased to meet Mykaell S. Riley of Steel Pulse at the conference; now a professor at Westminster, Riley delivered a keynote on his current AHRC-funded project Bass Culture. I also thought it is a fantastic to encounter the great interest from fellow researchers at IASPM XX in Riffs Journal and the Songwriting Studies Network associated with the Popular Music Cluster at Birmingham’s BCMCR: both served as points of reference during informal conversations and panel discussions.

Together with Andy Bennett, professor at Griffith University, I hosted a panel at IASPM XX and it took place on the second day of the conference. The title was “Music scenes, memory and emotional geographies”. With reference to a range of music scenes in Europe, Asia and Oceania, this panel examined memory-centred narrative construction, enabling new ways of understanding mythmaking and romanticism, integral to the collective importance inscribed in music scenes’ physical, symbolic properties and beyond. The panel included Andy Bennett’s paper on “Music scene spaces and emotional geographies: New cultural meanings through affect and memory”; Ben Green’s “‘My connection to the world’: Peak music experiences, place and scene”; and Mengyao Jiang’s “Emotions and identities: Understanding diasporic Chinese youth’s rock music practices in London, UK”. The title of my contribution to the panel was “The Canterbury Sound: Constructing Narratives of Place and Scene in Popular Music”. The phrases ‘Canterbury Sound’ and ‘Canterbury Scene’ are used to refer to a signature style emerging in the late 60s and early 70s within psychedelic, jazz, and progressive rock, developed by bands such as Caravan and Soft Machine with artists including Robert Wyatt and Kevin Ayres. This paper drew upon on ethnographic fieldwork, alongside a series of perspectives included in the upcoming collection on the Canterbury Sound I am lead editor for. Accessing networks of musicians, intermediaries, researchers, DiY archivists, and audiences linked to the Canterbury Sound, the paper suggested that myth-creation is reinforced through music memory reflections; retrospective evaluations of the genealogies of music scenes; the ways in which music is written about; and perceptions of desired cultural alternativity, continuity, and heritage. Affirming the distinctiveness of the Canterbury Sound in popular music imagination as an emotionally constructed space for individual and collective identifications, this paper addressed the cultural politics of negotiating place and music, genre and experimentation, memory, and aesthetic legacies. My presentation was well-attended and the passionate performative style of delivering the paper seemed to play an important role in terms of inciting the curiosity and involvement of conference participants in the audience, as they were central to the comments I received alongside a series of useful questions which I am intending to incorporate when finishing the introductory and conclusive chapters to the upcoming edited book. Receiving useful feedback and suggestions has been very beneficial for me, as has been the opportunity to promote the upcoming publication of the collection.

For me, the visit to ANU was made even more special by a tour of the music/recording studios facilities as well as the National Film and Sound Archive on site. Alongside the excellent panels at IASPM XX, conference organisers had planned a fantastic programme for the evenings including short takes on Australia/New Zealand popular music series; film screenings; a night with the rapper and comedian MC Digga, whom we had previously seen deliver a paper as Benjamin Morgan of RMIT; and a conference dinner at Canberra’s beautiful National Arboretum, beneath some of the starriest skies I have seen. The culmination of the entertainment programme of the international conference was, undoubtedly, the closing karaoke party led by Scott Reagan at Canberra’s coolest (for me!) venue – Smith’s Alternative. It was incredible to see fellow researchers in a completely new light – certainly some excellent singing and performance skills were demonstrated on stage that night. Considering the specialist popular music research context, this undoubtedly was the most self-reflective karaoke I ever took part in. My contribution was an eclectic as it included Tina Turner’s “Simply the Best” and Black Sabbath’s “Paranoid” (as a duet with Mark Percival of Glasgow University) which received flattering reactions. For me, the most memorable performance was Franco Fabbri’s interpretation of Bowie’s classic “Life on Mars” which evoked a great emotional response and loud singing/dancing along. The night continued with the excellent set by Geoff Stahl, whom I had previously seen DJ at Porto ’s Keep It Simple, Make It Fast, and an impromptu jam session by conference participants with instruments provided by the venue.

I have been left with wonderful memories from Canberra, even though the city is not among the most popular with Australian participants in the conference: many considered it “artificial”, government city, that lacks the life and curiosities of cosmopolitan cities like Melbourne and Sydney. According to me, however, Canberra has a lot to offer, particularly regarding University-related student, research, and art cultures. I will also keep with me the images of three winter sunsets that revealed unforgettable palettes of colour: one seen from the roof garden of the Australian Parliament building (free to visit!), Telestra Tower atop the Black Mountain; and Mount Ainslie, only a short hike away from popular War Memorial, and populated by some pretty happy-looking free-range kangaroos.

Re-Thinking Progressive Rock

Leaving Canberra after a productive, busy, and wonderful week was difficult; yet, I was happy and excited to return to the beautiful (and all-year-round warm!) Brisbane. Last time I was there, I was approaching the end of my PhD and travelled to take part as a guest speaker in two symposia – one on Popular Music and Resistance and another on Youth Histories. More than three years on, I visit Griffith University as an invited speaker again, this time at Andy Bennett and David Baker’s Rethinking Progressive Rock symposium. And while the topic might seem specialist and history-oriented to some, the event attracted a diverse group of international researchers, keen to address universally relevant, timely themes such as progressiveness in popular culture; genealogies of style; the significance of challenging and re/-defining genre categories; and the notion of aesthetic legacies. For me, as a scholar interested in the significance of local context, the papers presented by Sasha Block and Mengyao Jiang on progressive rock in contemporary Russia and China respectively, triggered my musical and ethnographic imagination, leaving me curious for more. I was also excited about the final panel from the symposium, which addressed one of the most well-known oppositions in popular music mythologies: the (supposedly) “virtuoso” and pretentious progressive rock versus the expressive, fast, and simple punk rock, often interpreted as a reaction to the complexity of progressive rock. Andy Bennett, Mark Percival, and Ian Rogers did a fantastic job in addressing the perceived dichotomy with both humour and critical awareness, highlighting how the two genre categories have drawn upon and influenced each other, beyond their seemingly strict boundaries. At the symposium, I was also pleased to meet two North American speakers – Timothy Dowd and Kevin Holm-Hudson – who had specially to take part. Their papers – Dowd’s sociological take on the creation of a prog cannon, and Holm-Hudson’s evaluation of perceptions of future in electronic and progressive music – were both excellent contributions to the event.

The paper I presented at the symposium was under the title “Progressiveness and Alternativity in Popular Music: The Canterbury Sound”. It explored the contemporary meaning of progressiveness as a popular music site where diverse approaches to innovation and challenging genre conventions interact. It was argued that “progressive” has evolved into a holistic cultural field, gaining legitimacy through its associations with perceptions of alternativity. My paper, presented at the opening session from the Rethinking Progressive Rock symposium, discussed progressiveness in conjunction with alternativity in the context of heritage and contemporary incarnations of the “Canterbury Sound”. The “Canterbury Sound” drew upon but also contrasted the cultural image of the Cathedral City and is now part of an alternative heritage of Canterbury. Here, longevity is achieved through creating a symbolic inspiration space that encourages genre boundary-defying musical experimentation. The breadth of this progressive “legacy” allows for inter-generational, aesthetic links with contemporary Canterbury acts such as Syd Arthur and Lapis Lazuli, the so-called “New Canterbury Sound”, alongside musical milieux enabled by music nights like Crash of Moons and Free Range. As my paper on progressiveness and alternativity involved discussions of creativity, I suggested that as scholars we need to consider those concepts in the ways in which we write about popular music. Therefore, I began and ended by presentation with poetry pieces which I had produced as part of my work with the Write Club led by Professor Nicholas Gebhardt as part of the Popular Music research cluster at BCMCR. The two pieces were both inspired by my work on the Canterbury Sound and sought to emulate some of its signature characteristics through sound and rhythm. The positive responses and interest sparked by the approach to the paper presentation gave me an opportunity to include in discussions the role of publications such as Riffs for a progressive approach to cultural research.

My participation at the symposium at Griffith has resulted in an invitation to participate in an upcoming edited collection. I have also had the chance to, once again, continue to gather feedback and ideas towards the final stages of completing the Canterbury Sound collection with co-editors Andy Bennett and Shane Blackman. My stay in Brisbane included, of course, some extra music-oriented explorations, particularly of the West End and Fortitude Valley areas. Keen to maintain existing contacts, I got in touch with John Willsteed of the Go-Betweens, who kindly offered me a tour of the Queensland University of Technology Creative Industries precinct, particularly the music recording and performance facilities.

… and post-conference Sydney!

Following the two excellent research events in Canberra and Brisbane, I paid a short visit to a close friend in Sydney –Alyssa Critchley, who recently gained her PhD at the University of New South Wales, specialises in DiY music venue economies, and is currently working for University of Sydney. My first night in Sydney included an excellent tour of quirky small music venues with Martin Cloonan of Turku University in Finland and John Wardle, head of the Live Music Office, part of Australian Government. Visiting around eight places in Marrickville, New Town, and central Sydney, we enjoyed gypsy jazz, funk, rock, punk, and blues. The experience inspired me to go to (at least one) gig every evening I spent in Sydney; for example, following my music interests and preferences, I was particularly pleased to attend an underground metal event at a venue called the Valve, by invitation of fellow metal scholar Dr Tai Neilson. Reflecting on the dynamic musical experiences I had in Sydney, I have been left impressed and curious by the burgeoning small scenes and the variety of venues, the distinct DiY discourse and the keen and supportive audiences.

While in Sydney, I was keen to pursue contacts and friendships with fellow cultural researchers working in the field of popular music. I was very thankful for the hospitality of music researcher Brent Keogh who showed me around the recording and performance facilities at the University of Technology Sydney. I was also pleased to have the opportunity to meet Dr Toby Martin, who had very recently moved from Huddersfield to take on a position at Sydney Conservatoire, which I had the chance to explore. And while I was very impressed by the indigenous light/electronic music outdoors show I saw at Sydney Opera House, the most provocative multimedia experience I had in Sydney was at the Carriageworks art centre, which I visited with musician and researcher David Cashman. At the Carriageworks, I saw Drone Opera – a anti/utopian take on the eclectic merge of aesthetics of perceived future and past. It is indeed that complex, yet inspiring, relationship of future and past in popular music culture that seems to encapsulate my time in Australia in 2019, made possible through the support of BCMCR. Now I shall spend a lot of my Northern Hemisphere summer writing as the events and discussions in Canberra, Brisbane, and Sydney have been informative, inspiring, and motivating!