Memories Are Made of This; Music as ritual and the paradox of the triple present

Memories Are Made of This; Music as ritual and the paradox of the triple present

Matt Grimes

Abstract:

Drawing on some of Negus’(2012) interpretations of Ricouer’s (1984-88) ideas on time, narrative and the “paradox of the triple present”, I wish to explore, through the concept of what Negus refers to as “music as ritual” (2012, 492), the notions of memory and nostalgia; two things that are closely related to time and narrative but not attended to by Negus in his article. I will use examples from my ongoing research into British Anarcho-punk (1979-1985) to demonstrate how these two important and two closely linked concepts can be applied to the notion of music (listening) as ritual.

Memory and nostalgia

Garde-Hansen (2011) suggests that, as human beings, we like to think of our memory as a biological storehouse or bio-technical hard drive from which we can retrieve coherent data on demand, whereas she argues it is far more undisciplined and creative. Our memories are often triggered randomly in a fleeting and disordered way and the degrees of depth and accuracy are depending on what is triggering those memories. Ricoeur suggests that our memory is constructed around a set of narratives, where experienced events are turned into narratives through emplotment (Simms 2003, 105-106 cited in Negus 2012). This plot, Ricouer suggests, is central to the way we understand our personal and collective identity. We continually update, adapt and manipulate these narratives, based on both past and present events that we choose to remember or suppress. This state of ‘flux’, where those narratives are constantly shifting, is further impacted on by the very nature of Who? What? Why? When? Where? those narratives are recounted. In a sense, our memory operates to justify and legitimise through strategies of selective addition and/or omission, or framing of the narrative through the omission or emphasis of a casual chain of events.

Similarly Ricoeur argues that narrative provides a cognitive “grid” through which as humans we interpret, understand and give order to the chaos and uncertainty of temporality (1991, 338 cited in Negus 2012). I would suggest that narrative also provides us with a grid which helps us locate, structure, interpret, and make sense of those memories of the past. Ricoeur refers to our experiencing of the past as something that no longer exists but is perceptible as a residue or a cache of remnants of the past manifested in the present, through memory or the process of remembering. So it could be argued that our experience of the past, and our ability to connect with it through memory, is located in our association with the present.

Where time and narrative feature prominently in Negus’ article I want to turn attention to the notion of personal and collective nostalgia (Wildschut, T., Constantine, S. et al, 2006, 45) and its relationship with time, narrative and memory. It could be argued that nostalgia relates to sentimentality for the past, which paradoxically contains positive and negative emotions and, like memory, helps us connect the present to the past and vice versa. By drawing on our memories our present emotional state is to some degree determined by the memory of past events. Bower (1981) suggests that emotional feelings serve as retrieval clues for memories associated with that emotion; therefore it could be argued that music that evokes a more emotional response is remembered better. Nostalgia also typically revolves around memories with or involving others in a communal or group experience of which we were part which, I argue, reaffirms our attachment to community and collective/personal identity, both past and present.

Music as Ritual

Negus suggests that our engagement with music exhibits behaviors that are a feature of rituals, and in doing so help us to locate ourselves, understand our identities and deal with our temporality (2012, 492).

Small (1998 cited in Negus 2012) stresses the communal qualities of ritual and how those rituals allow people to collectively explore, affirm and celebrate their relationship to each other and themselves. Using the live performance experience as an example of a communal music ‘ritual’ and listening to recordings, or what Eisenberg conversely refers to as “private phonographic rituals” (1988, 42), I suggest there is a link between music as ritual and memory and nostalgia. My own research into British anarcho-punk (BAP) was partly stimulated by a renewed interest in BAP from the media and music consumers. The research involves methodologies such as in-depth interviews, with previous participants of that scene, where issues of time, memory, narrative and the discourse of nostalgia feature prominently in discussions around ageing within music scenes. I suggest that these issues are central/key to understanding the participant’s relationship with the past, the present and the future. This interviewing process has required the research participants to reflect back on the historical moment of the past through the recollection of memory that is grounded in the present.

More often than not for my research participants the process of recollection or remembering has mostly followed a linear pattern, where they have tended to recollect past events in a chronological order. Negus suggests that linear time is the process of unfolding in a straight line with people and things occupying points on that line and unable to return to a previous point on that line. (2012, 489). Whilst I agree with Negus, in so much that we are unable to ‘physically’ return to a previous point on that line in present time, our memory can help, and in some cases allow, us to re-imagine ourselves at a particular previous point and thus consider time as circular as well as linear. This can manifest itself in hearing a particular piece of music and it transporting us back to a particular remembered or re-imagined point in time, with music being the stimulus or the carrier of that memory(s). So although we are not physically returning to that previous point on the line our memory allows us to ‘re-imagine’ that moment and help us construct a narrative of that past moment in the present.

All of the respondents in my research talked about particular pieces of music being stimuli for not only remembering specific events from their past experiences of the BAP scene, but also as a way of connecting to those times past. So for many people music seems to be an influential memory cue, (Schulkind, Hennis, and Rubin (1999). Adam (2004 cited in Negus 2012) suggests that music is used to evoke memories it also serve as a resource in the pursuit of memory by connecting the present with the past and I would suggest vice versa (493). Janata, Tomic, and Rakowski (2007) reported that music and songs frequently evoked memories and that one of the most common emotional responses named was nostalgia. Taking these two closely linked concepts I will apply them to the notion of music (listening) as ritual.

Alongside this renewed interest in BAP a large number of ‘original wave’ anarcho-punk bands have reformed to perform after being inactive for many years. For a number of these bands, there seems little desire to record new material but only to go out and perform. I asked my research participants their opinions on bands reforming and performing again. One respondent, who was returning to performing with their original band after a 30 year hiatus stated that this process of reforming was, for them, very much based around nostalgia and revisiting the past. This included the thrill, excitement and buzz of performing in front of an audience again and recapturing some of that earlier spirit and energy, whilst it could be argued celebrating that moment of the “present in the present” (2012, 487). Even though that involved them performing songs penned over 30 years ago they felt that the political intent of the lyrical content, albeit slightly naïve, was still relevant today as it was then, however they had no interest in writing new material. For this respondent listening to old anarcho-punk recordings also held the same values

“I do listen to anarcho-punk nowadays, though when I am on my own as my partner doesn’t like it so much….. Having kids it seemed that I lost myself in family life. It has helped re-focus me. I listen to the lyrics and they seem as relevant now, in fact the political messages just reinforce my beliefs and I see them from a different perspective- I understand them better now through the mind of an adult”

One of the other respondents when also discussing songs from that earlier period stated

“For me the musical and lyrical content still resonate, it speaks to me in a very base emotional level and is the most powerful influence on my life of anything, books. film, art. It’s a sort of touchstone for living without having to think about it-it’s a personal politic informed by anarcho-punk”

I suggest that this reference to the lyrics, or indeed narrative, of the songs is conveying experience of the past in the present but more importantly perhaps, as Negus suggests, “songs seeking political persuasion or engaging in social commentary may convey a comprehension of the present of the future as a desire for a better world” (487). The desire for a more ‘utopian anarchistic’ society without power, greed, poverty, control etc featured heavily in a large number of anarcho-punk songs of that period. This suggests that for a number of my respondents some of the associations with the past have remained and continued or, as Ricoeur would argue, are the traces or remnants of the past in the present; therefore perhaps making it easier for those respondents to make sense of them in the present.

Two other respondents were more critical of the notion of bands reforming and the nostalgia associated with it. One respondent stated that

“I am not big on nostalgia, and for quite a while I resisted seeing bands who had reformed just because if they are shit it will ruin my memories and opinions of them. It is nostalgia; though when people say that, it always seems a bit sad and desperate trying to recapture or recreate something from the past.

The other similarly critical stated

“I did go to Rebellion last year (an annual 4 day punk festival in Blackpool which has a number of ‘old’ punk bands that ‘reform’ each year only to perform there) and I was slightly challenged by some what I saw. There is a lot of nostalgia there, if I’m honest. Simply to reform a band and play the set you did 30 years previously for me is not good enough, there needs to be something else, there needs to be a freshness”

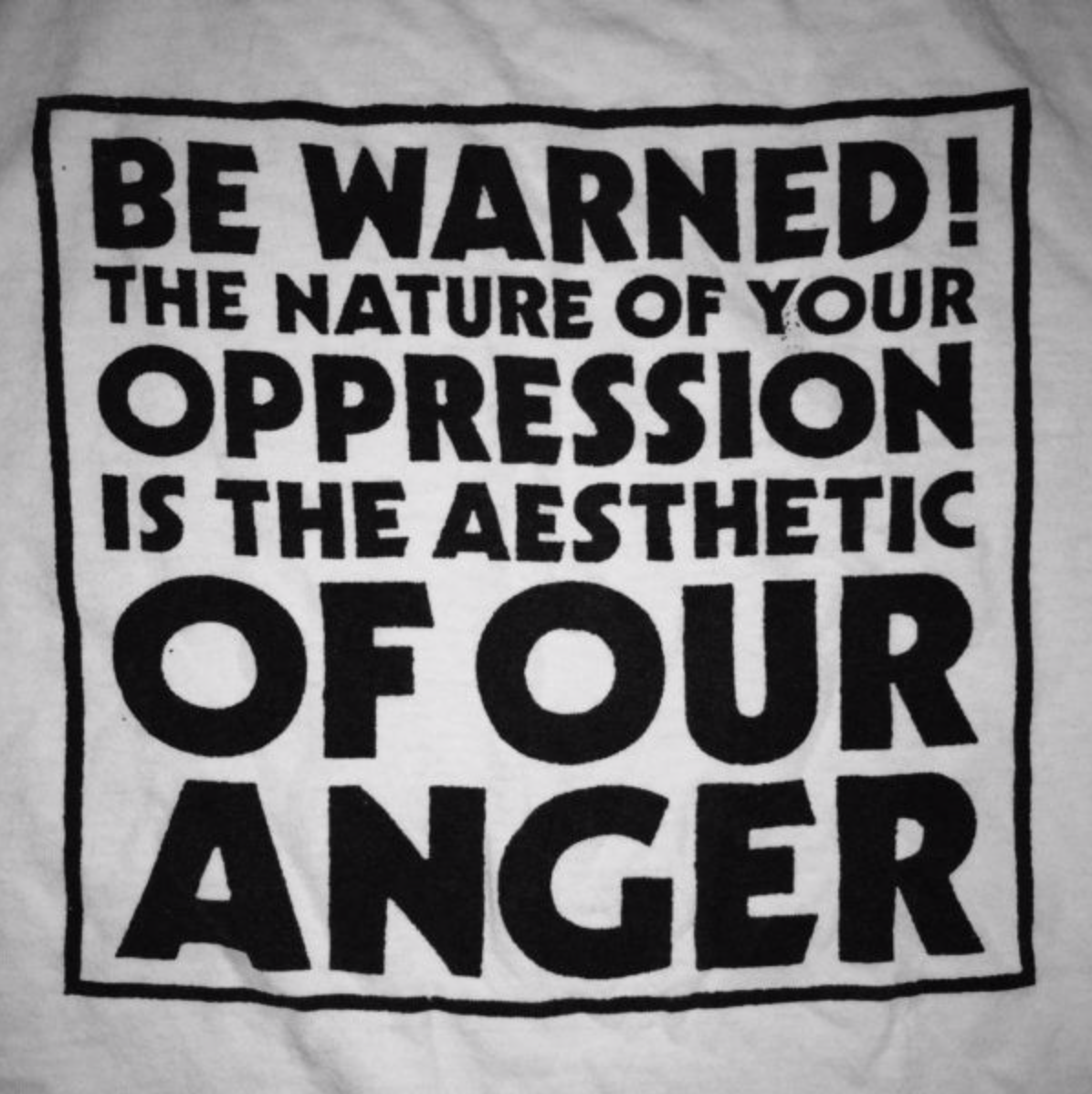

Similarly, through my own observations at a number of recent live performances of ‘reformed’ anarcho-punk bands, it seems that the live performance aspect gives the audience a sense of experiencing the past in the present. Interestingly at these live performances, the majority of the audience was male and in their 40’s and 50’s, so many of them would have experienced watching the bands in the 1980’s. A large number of them were wearing old T-shirts with the logo of the band performing or other bands of that past era. One could argue that although this is a display of fandom it also conveys an experience of the past in the present. Similarly a large proportion of the audience were singing along to the songs and reciting the lyrics, punctuating particular words or lines synchronously, conveying that experience of the past in the present, and which seemingly played a large part in the ‘nostalgic’ experience and the communal experience discussed earlier by Small (1998). Frenetic dancing and pogoing, as was/is associated with punk music, was not so prevalent within the audience, so perhaps where age has limited their more physical engagement, the personal connection between the past and present is maintained and displayed in other ways.

In this paper I have briefly explored the notions of memory and nostalgia in relation to Ricoeur’s theoretical approaches to time, narrative and the paradox of the triple present by applying them to some examples from my ongoing research. In this I have demonstrated how those notions connect our experiences of music between the past and the present, and suggest that memory and the evocation of nostalgia, through music as ritual, play important roles in how ageing fans of music make sense of the past in the present.

Bibliography

Bower, G.H. (1981)Mood and Memory. American Psychologist, 2, p129-148

Garde-Hansen, J. (2011) Media and Memory. Edinburgh. Edinburgh University Press

Negus, K. (2012) Narrative Time and the Popular Song.Popular Music and Society. 35(4) 483-500

Ricoeur, P (1984-1988) Time and Narrative (Vol 1-3). Translated by McLaughlin, K. and Pellauer, D. Chicago. University of Chicago Press.

Schulkind, M.D, Hennis, L.K, Rubin, D.C. (1999) Music, emotion, and autobiographical memory: they’re playing your song. Mem Cognit. 27(6):948-55.

Small, C. (1998) Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening. Hanover; Wesleyan University Press.

Wildschut, T., Constantine, S., Arndt, J., & Routledge, C. (2006). Nostalgia: Contents, triggers, functions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 91(5), 975-993.