Material Reflections – Robert Kendall’s Map – Nicolas Pillai

Material Reflections is a collection of short reflective pieces exploring the complex personal relationships that people form with material things. Bringing together perspectives from a range of academics, students, and cultural practitioners, the project seeks to highlight the breadth and plurality of ways in which material things impact upon our ideas, identities, research, and practice. This Material Reflection comes from Nicolas Pillai, who is a research fellow specialising in jazz and visual culture. In it, he reflects upon a souvenir, its location within space, place and time, and the fine line between a mundane object and a work of art.

I was sitting at the bar downstairs at Small’s jazz club on West Tenth, sipping a pale ale, pretending not to be a tourist. Nearer to the stage, a waitress was enforcing the one drink minimum, leaning across the serried seats with her notepad. I’d elected to order direct from the bar, perched up on a stool above the shit-munchers.

Róisín came back from the bathroom. “Give me some money, “ she said, turning as though she wasn’t planning to take up her stool next to mine. I peeled off some notes from our daily allowance and she darted back to the doorway at the back of the room. I took another sip of beer and pondered what kind of transaction might occur in a New York public bathroom.

Five minutes passed and the band had started playing. Róisín came back from the john. This time she was carrying a New York City Subway Map which she planted triumphantly on the bar in front of me. “I bought you something,” she announced.

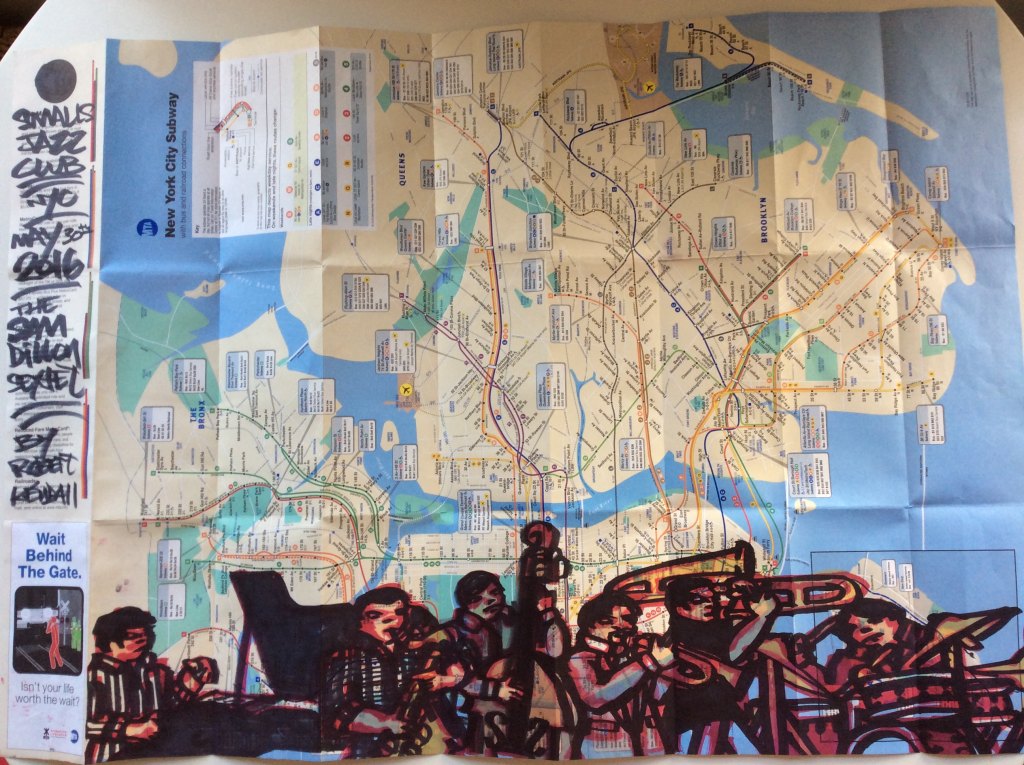

The New York Subway Map being free and readily available around the city – I had another one in my back pocket at that moment – made this gift initially underwhelming. But when I opened out the map, taking care not to nudge the drinking elbow of the guy on my right, I saw that this wasn’t just a map. Turned so that Manhattan lay on its side, spread horizontal rather than vertical, I saw that the map was a canvas onto which somebody had drawn a jazz band. Not the guys who were playing right now: scrawled on a panel in graffiti script was yesterday’s date and the legend The Sam Dillon Sextet. Underneath was another name: by Robert Kendall.

On that map, drawn over Manhattan, with Brooklyn hovering like a cloud behind them, were six men depicted in marker pen. A pianist, a saxophonist, a bassist, a trumpeter, a trombone player, a drummer. Each was picked out in different colour highlights, crudely but effectively. I found myself more interested in the band on the map than the band onstage.

In the interval, we went back to Robert Kendall’s nook, set into the corridor next to the restrooms. Every night he painted that night’s band onto maps, eye-charts, drum-skins and sold them. Until recently he’d been homeless. “Music is visual, of course it is,” he told me as we posed for a photograph together.

It was a mistake to go back to Small’s a few days later. We couldn’t sit at the bar, Róisín was uncomfortable, we argued. I said hello to Robert on my way out but he didn’t recognise me. It was the last night of our holiday.

I framed the map when we got home and now it hangs in our bedroom. It’s the first piece of art we ever bought together: a map that you can’t use, a record of a band that we didn’t see. I’m worried that over time the ink of the markers will bleed further into the paper, that the drawing will lose its resolution. But memories are like that, I suppose.