“Groove The City: Constructing and Deconstructing Urban Spaces Through Music”

Last week I travelled to the town of Lüneburg in northern Germany for the ‘Groove The City: Constructing and Deconstructing Urban Spaces Through Music’ conference, held at the Leuphana University of Lüneburg.

This was the second time the conference has been organised, with the first taking place in 2018. Broadly the conference aims to set out and develop the field of Urban Music Studies. This emerging field is interdisciplinary, drawing in scholars from numerous areas, including Sociology, Urban Studies, Musicology, Geography, and Popular Music Studies. The conference in an opportunity for scholars to tie up different disciplinary perspectives and to develop collaborations. It is where ideas of the intrinsic logic of a city – the rules, systems, and so on, under which a city functions – meet with considerations of the ‘spirit’ of the city. Music is central to this overlap; it helps shape the logic and the spirit of the city. But, crucially, this is also a process that works the other way around, where the spirit and logic of the city informs the music that emerges from it.

I was presenting some research I’ve been working on with my BCMCR colleague, Nick Gebhardt, about the use of mobile applications at music festivals. My paper described and reflected on the methodological process of creating several different versions of a mobile application with project partner festivals. In this work we have attempted to address questions of sustainability for jazz and improvised music festivals, whilst also examining the practicalities and questions that arise when a new digital technology is introduced to a festival environment. In the context of the conference, a festival space can be considered a ‘city’ in that it temporarily comprises many of the things (infrastructure, people, and so on) that constitute a city. In the case of our work, too, several of the festivals we have worked with actually take place within city environments. They are events where the logic and spirit of a city meet through music. One of the other things I wanted to discuss within that context was the idea that mobile devices are powerful tools, particularly when allied to the data collection they help make possible. I attempted to describe how we have engaged with questions of data privacy, ownership and ethics when working on the functionality of the apps we’ve developed, and how the ‘city’ space of a festival provided the canvas for that research.

The paper was well received and generated some very interesting questions from my fellow delegates. One in particular related to how the app will develop in future, and whether the evident commercial potential of the software can sit alongside a critical research process. This was a welcome question as it is something we have been considering lately with our project partner, 1UP Design. Other questions involved the broader use case for applications at arts events, and how these technologies can be utilised alongside other activities around audience engagement and development. The lively discussion this generated gave me some useful things to think about as we move into the next phase of our research.

As a delegate at the conference I also enjoyed a number of papers from colleagues across the world that gave me useful, new perspectives that will feed in not only to the work we are doing with mobile apps and festival, but also in my current work with Patrycja Rozbicka and Adam Behr around the live music ecology of Birmingham, and in my work with Simon Barber and his Songwriting Studies Research Network. Shane Homan from Monash University, Australia, gave an excellent paper on the ‘Agent of Change’ principle involved in disputes between music venues and property developers, illustrated by fascinating case studies from Melbourne. Arno van der Hoeven from the Erasmus School of History, Culture and Communication, Rotterdam, Netherlands provided a wider perspective on this issue with his paper about the representation of spatial value in live music. In my discussions with Shane and Arno afterwards we saw considerable overlap in our work, and recognised that – despite the different local contexts – the issues facing music scenes are largely similar. I’m hopeful we may be able to develop some further work in this area.

There was lots more to enjoy at the conference: Melanie Ptatschek’s paper on the social function of buskers on the New York subway; Ina Kahle’s work on how music festivals provide a space for critical reflection for young visitors, and an excellent and entertaining keynote from Jennifer Lena around approaches to genre. The organisers of the conference are currently planning a book series and several other publications and future events. On the evidence of the last few days will certainly be something I will pay close attention to. You can find out more about their work by visiting www.urbanmusicstudies.org.

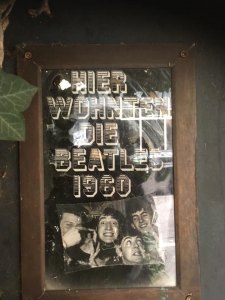

On my way home, travelling via the city of Hamburg, I had the opportunity to spend a couple of hours exploring the places and venues that hosted The Beatles in 1960. As a far as I could tell there is no ‘official’ tour, so I had to create a route for myself following a little bit of research. In what felt like a footnote to my paper, this involved me following a dot on my mobile phone through a succession of tiny side streets, hunting for addresses I’d found from Beatles-related blog posts. In particular I enjoyed visiting the house the band first lived in, a run-down structure covered in ivy with a partially-hidden sign that simply says, “The Beatles lived here 1960”. This little detour provided the ideal end point to my trip, as it perfectly illustrated the idea that music and the city are inter-twinned in often subtle but nevertheless complex and fascinating ways.

Dr Craig Hamilton