Principles

- Archive retrieval is time-consuming, but rewarding

- An archivist or research assistant will have skills and experience to help

- Take time to plan your search of the archive: start with an expansive list of keywords

- Be prepared to think creatively about how to use the available material

- Allow lead time: archive staff field many requests and will take time to respond

How do you find something in an archive?

If you are able to work with a research assistant (RA), they will have skills and experience to lead this part of the process. If you don’t have access to (or funding for) research help, you can do archival work on your own. Archives such as MACE make their search functions public, and do not require special access. Some archives are, however, closed to the public; but you may still be able to contact an archivist and work with them to retrieve relevant material.

This section will use more detail from Generations of Commemoration and MACE as an example of how to access an AV archive.

There are (broadly) two stages to working with an archive: finding out what material is available, followed by selecting which items to request for closer study. On Generations of Commemoration, this process happened a few times. Guided by the project brief and discussions with SCA, our RA used MACE’s search functions to create a master list of all the clips which might be useful, and made recommendations to SCA about what holdings should be requested for use. The RA then contacted MACE directly to learn which films could be used for this kind of workshop (i.e. were licensed to be used in this manner). Seven films were then made available to SCA, who screened them all and selected one short film to use in the workshops. This film showed the 1927 dedication of the Alfreton War memorial.

Step by Step: Finding the Film

Finding something in an archive is not difficult, but it is time-consuming.

What follows is a description of the process followed on Generations of Commemoration in search of Great War material. This is of particular relevance to those using MACE, but many of the steps apply to any kind of archival retrieval.

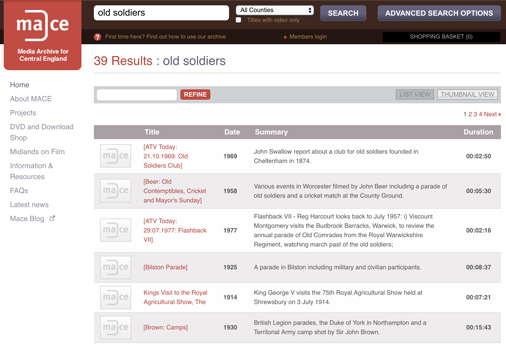

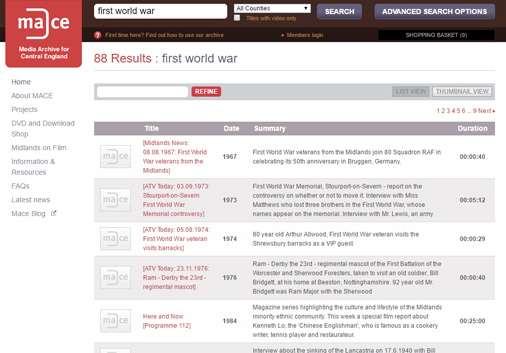

1. Comb through archive search results, collecting all possible references to your topic (here WW1)

- Start with list of provided keywords, which were drawn up as guidelines

- Modify search (narrow/broaden) based on what terminology is used by the archive (“home front” giving results for “national front”; “Great War”, “old soldiers” for interwar material)

- Descriptions of material can be as old as the material itself: be prepared for out-dated language

- If the archive uses tags, as MACE does, browsing these will connect you to parallel material or new sets of keywords, such as “Old Contemptibles” as a synonym for WW1 veterans

- In addition to WW1 searches, our keywords also included the neighbourhoods of the schools themselves, fitting SCA’s established practice of working with hyper-local history based in the built environment.

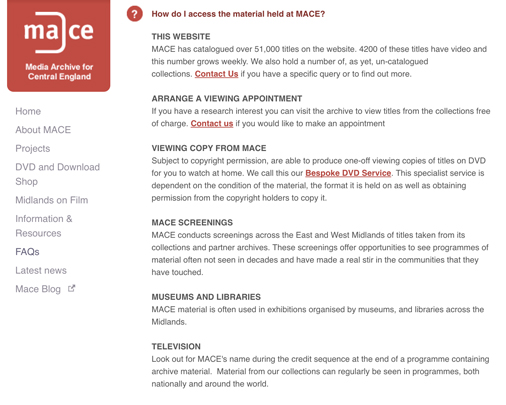

2. Contact the archive via email before you get too much further

- Offer a quick introduction to your project, explaining what its goals are

- Find out what provision the archive has for making films available for education or research, and what their typical timescales are for releasing copies

- Communicating in the early stages of research also helps the archive plan their workflow, and makes it less of a surprise when you bombard them with requests

- For our project, physically visiting MACE wasn’t necessary as all business could be conducted online.

3. Keep your list in a separate file, pulling in as much detail as possible.

- Note every relevant record with its identifying number as you go

- This gives you a document to refer to, meaning you don’t have to continually return to the search page

- We noted data such as title, duration, brief description, and stable URL for each film’s record

- Our longlist of results was more extensive than just those films which had a direct mention of WW1, since the scope of the project was to evaluate the changing remembrances of that conflict. Accordingly, the list also included news magazine programme discussions of how commemoration has changed, interviews with veterans, and a selection of later 20th-century remembrance activities which are likely to mention both WW1 and WW2

- Keep the list as expansive as is reasonable at this stage

- Don’t get discouraged because the kind of film you hoped to find hasn’t turned up in the search results. It may never do, but you have to be open to seeing what is in the archive, rather than what you would like to be there.

4. Analyse results, evaluating relevance

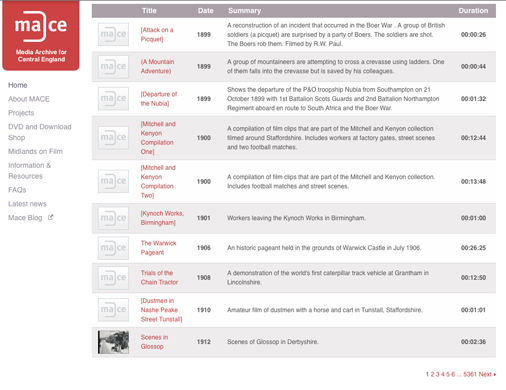

- It can be useful to sort the records. We did this by year and by theme

- What kinds of films are available (home movies, newsreels, factual broadcasts, human interest stories)? What patterns emerge?

- A lot of information is available in each film’s record: decisions at this stage are not based in viewing the films themselves

- With an AV archive, recording duration is important – MACE collects home movies, news magazine reports, discussion programmes, amateur films, etc. It may be more expedient to simply note the existence of a 15-second clip that is listed in the index (e.g. women window washing, 1915) but to request a longer film for viewing, as it may give you more to work with

5. Draw up preliminary list of highlights

- Note items of exceptional interest

- Meet with project partners, discuss what is available, and what different film selections might mean for the direction of the project (do the films have sound? What decade are they from? Will that matter?)

- Narrow selection further!

- On Generations Of Commemoration, at this point we had a list of 15 possible films.

6. Forward list to archive to find out what is available

- Build on the connection you made back in step 2.

- The archivist will let you know if the films have been digitised. If not, you can discuss how long will it take to convert them, and whether or not this would incur extra costs.

- Are there alternative films that have already been digitised, and are therefore more readily accessible?

- Are the films subject to licensing fees? Who owns the rights?

- The archivist may suggest further options that you hadn’t come across, or that you’d dismissed in your earlier selection. If these can be viewed without further expense, say yes to these too!

7. Evaluate new, shortest list

- On Generations Of Commemoration, our goal was to generate sufficient useful material for a schools project, and to demonstrate what kind of material archives may have readily available

- We didn’t follow up the availability of every film, due to time/budget pressures, as there was a healthy selection

- On a different kind of project with a different budget, there would be potential for more active pursuit of a specific film. On our project, there was more scope to look for something indicative or evocative

- Deviance from the original brief is fine, if the film looks promising: the Alfreton film chosen proved to be a much richer text than the ones shot in Birmingham

8. Almost there!

- Sign and return clearance paperwork provided by the archive

- Obtain correctly encoded (for us, mpeg4) copies of the shortest shortlist of films, shared with partners so they can make final decisions

- If receiving files through a digital locker service, be sure to save a copy locally: these sites will delete the files after a short interval (WeTransfer has a 7-day window to access shared files)