Principles

- Anyone can produce history

- Public history work can go beyond familiar stories

- Historical work can be accessible and creative

What is Public History?

Everyone has a history that connects them directly or indirectly with stories from the past about the wider community – locally, nationally and globally. Alongside the work of professional or academic historians, there is a wide array of other ways of representing this connection with the past, as well as many ways of engaging non-professional communities.

This array is often called ‘public history’: it is produced by individuals and communities, who need not be professionals, as a public ‘event’ which attempts to engage as wide a constituency as possible. Whether concerned with the Great War or some other aspect of the past, anything can be the subject of history and can be conveyed in a range of interesting and meaningful ways. The work of public history includes historical re-enactment societies, blue plaques, musical tribute bands, drama and so on.

Seen in this way, then, public history offers a space for everyday, ordinary and often overlooked stories to be told in creative ways.

Pyn Stockman: As a subject, World War I is not necessarily studied or explored in primary school at all. So, I think what we wanted to do with our project wasn’t to focus too much on the war aspect, but to focus on the home front and what would have been going on.

Mandy Ross: Initially, a head teacher had said, “Oh, no. We don’t do World War I in primary.” So, that was useful to learn, and certainly, I think you can offer it as, “These are different ways of getting kids fired up about history.” That’s a more general thing that you’re offering, with some CPD for teachers, than simply, “Here’s a bit of poppies and bloodshed about World War I.”

The centenary of the Great War provides the backdrop to this toolkit explored in the supporting case study of Secret City Arts activity on Generations of Commemoration. Although many people would be able to trace personal connections to men who fought on the Western Front, the history of the First World War is about much more than the mud and trenches: it is about other theatres of war, about the wider impact of mobilization on countries like the UK, about the families supporting men at war, about women and children working in factories or learning in schools, all amidst this traumatic event. Then, of course, we can imagine the legacies of the war: for those who came back; for the families waiting for them; for the families who lost sons and husbands. Seen in this light, the idea of the veteran encompasses all those impacted by the war, and its meanings are not confined to 1914-18 but endure in memorials and around a century of annual commemoration. This process and practice of remembering might, itself, be a form of public history.

While academics are core to work on Voices of War and Peace, the projects it supports (exemplified here by Generations of Commemoration), and SCA’s practice in particular, suggest a range of activities that we can count as ‘public history’ and demonstrate the variety of ways in which history can be produced. SCA, for instance, outline the differences between ‘academic’ history and the nature of their own public engagement work:

Mandy Ross: What we look for are tiny nuggets of history: tiny bits that we can then weave a story or invite the participants to imagine a story around. So, I think that’s a very different approach from an academic history. So, it’s very much a starting point, a historic document or an archive resource. It’s one tiny thing.

Creative Public History

Public history approaches, like those demonstrated by SCA, allow for overtly creative interpretations in order to develop ideas about the past. Although they do not ignore the importance of facts or the ‘correct order’ of events, such approaches do not necessarily make a fetish on these aspects of history. Instead they seek to make connections between individuals and events, between the general and the particular, in highly personal ways.

SCA aid an understanding of the past through creative activity, a practice that is apparent in the educational aspects of their work with children. In the Generations of Commemoration project, their work has involved both pupils and their teachers, and has extended the knowledge of both beyond the limits of the national curriculum and how it deals with the Great War:

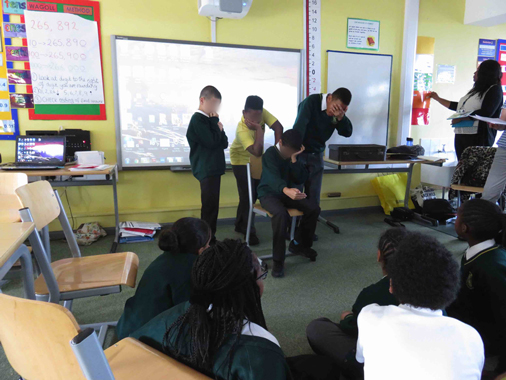

Mandy Ross: What we’re trying to do is to bring the history to life and for the children or young people to inhabit a story, so that they have some empathy with the characters. And they can try to imagine what they might do if they were in that situation, imagine what it might have been like. [Pyn’s] drama work […] is all about experiencing some of the feelings that go with that kind of experience. So, making connections.

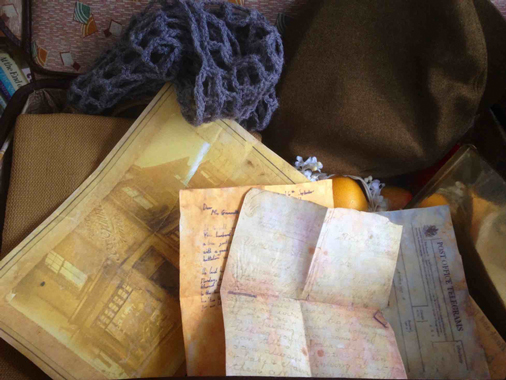

Pyn identifies the combined use of physical materials and everyday objects (such as suitcases and documents) alongside creative writing or film-making as integral to telling a story about the past, of setting the personal within a wider context of understanding:

Pyn Stockman: We tell it as a story. We create that bit of excitement of, “This case. It contains a story. A real story,” and from that moment, the kids are kind of, “What? What?”

Then, they wait for the reveal, and then gradually the objects are taken out and the objects, the artefacts… They help bring that story in some way to life. The children get to interact with those, not just in a, “Oh, we’re looking at an old letter,” but, “This tells us something about what we’re going to work with.”

Then, the drama work goes on to ask them to become those characters: “What is it like to be that character? What do they do? How do they do it?” So, you begin to gradually build up a picture, and I think maybe that’s slightly unusual.