Principles

- Archives collect historical material and take many forms

- Many official archives are open to the public and are resources available to all

- Archives are interpretations of the past and what ‘counts’

- Archive holdings do not have a ‘perfect’ fit for project ideas

- Archives are creative resources

What are archives (and how can we use them)?

An archive is a collection of materials that offer a resource through which we are able to describe, interpret and understand the past. Archives may resemble the materials presented by museums, or may be akin to the collections many of us keep of family photographs, or to the records that we have from the formal and informal organisations to which we belong: our school achievement record; a weekend netball or football team roster; notes from a book club.

Historians tend to work with archives that are maintained by national and local government and so have a formal, legal status. These archives contain the documentary evidence of how things were organised and managed in the past, and their material is properly catalogued and searchable. The National Archive, for example, contains the material that often informs official histories of the nation and of the great and good. Nonetheless, such archives also preserve material that tells other stories.

But no matter how ‘formal’ and well organised they are, archives are not exhaustive repositories of the material of the past. As such, any collection to which we might turn in order to produce history – academic or public – invites a number of questions that are key to archive literacy:

- Who collected this material?

- How and why was this material chosen (what’s missing)?

- How is it organised?

- Who pays for this collection?

These questions underline the idea that archives are already an interpretation or ‘mediation’ of the past as by default they represent a selection of materials. Above all, the key question for public historians is: (how) can we access and use this archive? Public archives are, in theory, available to all, but there are limits on what can be done with the material they contain. The rarity or value of documents may mean that historians are not allowed to borrow them, for example, or to photograph or otherwise copy them.

Audio Visual Archives

Alongside those archives that contain papers and official documents are a range of collections that offer access to visual and audio records of the past. In the UK, these include some of the holdings of the British Library, the British Film Institute and the regional film archives.

One of these is the Media Archive for Central England – MACE – an accessible organisation which connects people with the moving image heritage of the English midlands. MACE does this by:

- selecting and acquiring, researching and developing moving images and related materials which inform our understanding of the history and culture of the midlands.

- ensuring this collection is accessible through the application of preservation and curatorial skills.

- providing public repository services, professional advice on the care and preservation of moving image heritage, and support for community-based events and collection-related research.

But we should also now recognise accessible resources such as YouTube and Vimeo as a form of archive, as well as social media sites such as Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and others connect which themselves connect with and collecting individual and community materials like photographs, video and sound.

One great benefit of the holdings of archives like MACE is the way they draw attention to the look and sound of the past: how the past looks and often sounds different!

Audio Visual Archives are interpretations

As suggested, archives are always interpretations: archivists generally collect only a fraction of the materials and accounts of the past, and cannot preserve everything. However, this means archives offer a perspective on what matters simply by virtue of the choices that they make. Furthermore, the documents held in archives are themselves interpretations: letters, diaries, reports and so on, alongside the ‘facts’ of ledgers and the like.

This idea of interpretation is useful in thinking about audio-visual archives like MACE in two ways.

Firstly, while the digital age appears to involve recording and sharing everything, the AV record of the past – in film, television and radio for instance – is limited. As historical material was stored on perishable media such as film or videotape, unless it has been digitised much of it is in danger of being lost, if it has not been lost already.

Secondly, whether with or without sound, or colour, the direct or ‘liveness’ of film, TV and audio recordings has the appearance of ‘reality’. It can be inviting to approach such material as if it is ‘unmediated’; but just with writing preserved in the archive, one also needs a form of literacy with which to view and hear film, TV and sound recordings.

Extending those expressed above therefore, basic questions to ask of AV archive material include:

- Who made this record?

- What kind of techniques were used in production (what can we see of it)?

- Who is in this film/audio?

- Who saw or heard this material (who was it for)? What did they make of it?

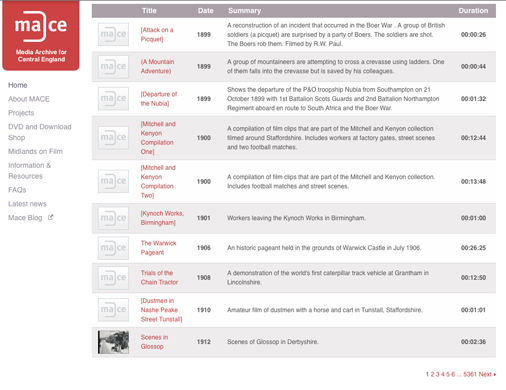

In the case of MACE, as with a variety of official archives, the archive catalogue is available online for users to search. A range of material has been digitised already, and can be viewed online; but the majority of holdings are not yet available in this way,

The general and particular in the AV archive

Many people encounter archives in everyday life when they embark on personal projects such as researching their family tree. There are plenty of highly individual and personalised records available to the amateur genealogist, of who lived where and in what street thanks to voting records, as well as birth, marriage and death certificates. Similarly, in a previous project, SCA worked with primary school children, drawing upon a specific school record book and memorial information regarding specific individuals.

Audio-visual archives are generally not so precise or democratic, and their material does not tend to identify individuals and specific places in the same depth as written archives might. While MACE, for instance, does have some (surprising) material of this nature as a result of holding local TV news archives, film and television coverage of ordinary people has historically been limited.

Holdings of the AV archive will, therefore, need to be used as general representations of the past, rather than as the kind of personalised evidence people used to produce family trees or to deliver SCA’s previous work. Don’t expect an audio-visual archive to hold a perfect film for your needs – of a very particular event or place. Instead, expect it to have a large number of films that you can approach with a sense of creativity and flexibility, and be open to letting the collection guide your selection. The act of interpreting what an archival film contains and what meanings can be extracted is a significant part of the process.

Mandy Ross: The MACE archive was something […] We were aware of it, but didn’t really have a sense of what there was in it, and also how we might build on our previous projects to develop further work.

Pyn Stockman: Ultimately, where film might sit when we do a bigger project and how we might use film, existing archive film, within the films or the live performances that we make would perhaps be one of the outcomes.

An added challenge for the work demonstrated by SCA lies in consideration of how archives may not be a reflection of who we are now. What if your personal lineage and community is not readily mirrored in the historical record?

Mandy Ross: In our project, originally, we were working with a school community where the families would not have had personal links with World War I. They would have come to this country much later and not have had personal involvement. We wanted to find a way to work out how to bring the history and the commemoration alive for people who wouldn’t automatically have a personal link.

In such instances, it is creative approaches that make historical engagement and understanding possible.