arch

Designs on Television

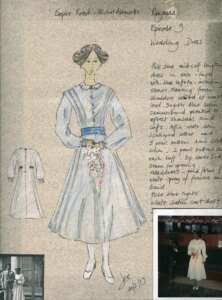

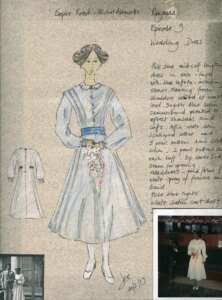

‘Empire Road’ wedding dress design by Janice Rider

I spoke recently at the ‘Designs on Television’ conference at University of Westminster. Few conferences focus on the work of television designers, so this was a refreshing event to attend. The majority of the conference concentrated on production design, but myself, and a couple of other researchers, examined costume design. My paper was entitled, ‘Creating Characters and Priming Performances: The Under-appreciated Roles of Costume and Make-up Workers in UK Television Production 1950-2000’.

Design on television, and particularly within the female-dominated departments of costume and make-up are under-researched in comparison to film. There is a body of scholarship on women’s below-the-line roles in film by scholars such as Miranda Banks, Deborah Jones, Judith Pringle, Helen Warner, Erin Hill, and Melanie Williams amongst others. In television there is significantly less work, and therefore less appreciation of the complexity of the roles within costume and make-up, and the creative agency of workers.

We can learn from the research that has been undertaken on film. Miranda Banks (2009) -talks of the invisibility of the costume designer’s work on-screen marginalising the recognition of their work. It is no coincidence that the costume profession is female dominated, leading to it being undervalued and often dismissed as ‘women’s work’. Erin Hill (2016), concludes that the occupational segregation perpetuates male domination in roles with the most power and prestige, whilst women’s roles have little visibility, and Melanie Bell (2021) notes that historically women in below-the-line roles are rarely recorded in official records.

It is therefore important that we build our own archives and unofficial records. One way of doing this is through oral history interviews, and drawing from some of the recordings I have made with costume and make-up designers, was the basis of my presentation. I set out to explore the creative contribution of women working in TV costume and make-up. The women ranged from in their 50s to their 90s.

Below is a comment by one of my contributors setting out what the work of a costume designer involves, and the importance of working collaboratively within a team:

“It was very rare you designed clothes. It’s about managing your budget and staff, working out how many staff you need. Fighting, you know, if they don’t want you to do this or do that. Planning. Obviously, the result of certain amount of design but it’s more in the way of being a social worker ….. There’s a lot of negotiating with the director, not so much for the producers, but with the directors, trying to get them to commit to things and because, you need to know what your budget is.

You’d get the scripts, and you’d work at those yourself. And obviously, you’d have to plot your days and do all that. So, where you were going get your costumes from, was it a costumier? Was it going out shopping? Was it hiring? Was it making? And then you’d have meetings. But yes, you need to get a visual idea and also chat with the design people just to see what their ideas were as well. So really very collaborative work”. Ann Doling: Costume designer.

This gives an insight into the complexity of the role. One theme which emerged from the oral histories is that the women often felt their work was under-appreciated, both by the production team and by management. This was manifest on screen, as in the early days of television, costume and make-up often went uncredited.

Costume Designer, Pat Godfrey mentioned that middle management were often dismissive of them, thinking of them as “silly little women in costume and make-up”. Another costume designer, Gill Hardie, described some members of the production team and crew thinking that costume and make-up staff, “were just a nuisance and got in the way”, because of making last minute adjustments to actors on set.

Working with actors whilst rewarding, could be also difficult, as you were managing anxious performers just before they went on set. Gill Hardie recalled the challenges of working with an actor who could be a bully, but was also very nervous and having to tell the odd white lie to manage his ego. For example, she pretended to re-fit a jacket that he was unhappy with, when it already fitted perfectly. Pat Godfrey talked about the challenges of working with actors with drink and drug habits. She was asked by production to look after an actor with a drink problem who insisted on going to the pub and she had to try and ensure that he did not drink too much. This seems to be considerably beyond the scope of the job.

Make-up designer, Susie Astle told me, “the work of preparing the actor for any role is vital, we are usually the last people to see them before they went in front of the camera. I worked on a documentary about the Birmingham pub bombings and one of the survivors interviewed was so nervous, I sat under the table and held her hand. Costume and make-up were good listeners!” Again, this would fall far outside the role, but illustrates the importance of the trust that can grow between costume and make-up workers and the people they prepare for camera.

Costume and make-up staff had to be quick-thinking and solve issues as they arose. Costume designer, Joyce Hawkins, recalled an incident that happened to her in the moments before a live television drama, starring a very young Judi Dench, in Hilda Lessways (BBC, 1959). “As Judi entered the studio her elaborate cascading bustle fell to the floor in a heap of satin and lace….as the direction “standby studio” rang out, I was on my knees frantically pinning it back up. Judi remained calm and I spent the scene huddled behind a sofa on set.” Whilst an amusing incident, it demonstrates the lengths required to make a drama look as good as possible.

The examples provided, show the breadth of work encompassed by costume and make-up staff. The complexity of the roles are little understood, particularly those elements which fall outside the actual ‘designing’, namely: organisation, negotiation and collaboration. In addition, costume and make-up play a significant role in preparing performers for the camera, both physically, in dressing and making them up, but also psychologically.

As all of this illustrates that there is plenty of scope for academic research around the creative work of costume and make-up staff, and I look forward to undertaking a portion of it.

Banks, M.J. (2009), ‘Gender Below-the-Line: Defining Feminist Production Studies’, in Production Studies: Cultural Studies of Media Industries, ed. Vicki Mayer, Miranda J. Banks, and John Thornton Caldwell (London: Routledge, 87-98, 91.

Bell, M. (2021), ‘‘I owe it to those women to own it’: Women, Media Production and Intergenerational Dialogue through Oral History’, Journal of British Cinema and Television 18/4, 518–537, 521.

Hill, E. (2016), Never Done: A History of Women’s Work in Media Production, New Brunswick, New Jersey, London: Rutgers University Press, 6.